I’ve only completed four marathons in my life. All of them were back in the days when I wasn’t a committed runner. It seems I was following, what is now, a familiar box-ticking approach to running. My first distance race was a 10K as parkrun didn’t exist then and 5K races were rare. But the sequence is standard – run a few races at a short distance then move on up to eventually do a full marathon. Now I realise training for, and successfully running, a full marathon is a big commitment if you want to do it well. Although I knew then you should do six months of training beforehand, I was only focused on getting the long run done. Again this is a familiar story of modern runners.

My last marathon was way back in 2010 and, for the first time in my life, I was beginning to train more regularly. I began the year by entering a twenty mile race which, when the train had demoralised me enough, I downgraded to ten miles. I followed it up a few weeks later with the Bournemouth Bay 1/2M in 1hr38+ at the beginning of April. To that date, it was the best race I’d ever done and knocked 12-13 minutes off my old Personal Best.

In the weeks following the half I began to lose interest in running and it was by entering the New Forest marathon, scheduled for late September, that I found motivation to get out and train again. I was in decent shape and with five months training, it should have been easy. In fact by early June I’d completed the twenty-mile run leapfrogging from fourteen to seventeen to twenty. I spoke with an experienced runner and he suggested there was no need to do the twenty miles every week and my records show I only did a fourteen mile run after that before disaster struck and I pulled a calf muscle. I lost the whole of July and it was early August when I could run again.

Suddenly I only had eight weeks until the marathon and I’d gone from having over three months to improve on my twenty mile long run to needing to rebuild entirely. Still believing in the necessity of the twenty mile long run but also recognising I couldn’t do it the week before the marathon I squeezed training into six weeks – 9, 11, 14, 17, 18, 20½, dropped to 9 miles and then ran the marathon the following week. I often say the reason it worked so well for me is because I didn’t have time to overtrain or under-recover!

On the day, two non-running moments stand out in my memory.

Firstly I arrived to collect my number which my racepack said was something like #1600. In the sportshall, I saw two collection desks one with a sign saying “Marathon 1-999” and “Half Marathon 1000-2000”. I was confused as my number suggested I was running the half but I knew this wasn’t the case. What most surprised me is how devastating this was to my psyche. I’d prepared for the longer distance, so if I had to run half the distance it would surely be no trouble. I could see it would be a problem if you’d only trained for a half and then found yourself expected to somehow do double the distance but, not when you knew you’d run over seven miles further in training. Somehow it was devastating.

I talked to the organiser adamant that I’d entered the full marathon while he said I couldn’t have; fortunately he was willing to move me into that race anyway. Once I’d got my sub-1000 number I felt calm about what was ahead.

The second issue was forgetting my new running shoes. Of course I knew you don’t run a marathon in a new pair of shoes, so I’d broken them in before the race. But I forgot to bring them along and ended up running the marathon in the old battered pair which had lasted me all through training. Oh well. I didn’t get any lasting injuries so no harm, no foul. Not good race day preparation though, yet not the first time it happened to me!

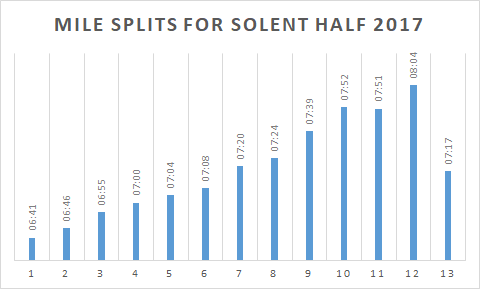

The race itself went well. Classic autumn day and decent conditions – sunny, warm and not too humid. I’d borrowed a Garmin from a work colleague and watched the miles tick by. I’m not sure whether I went into it with an intended time – I suspect I did as I’d begun to discover the online race calculators. Whether I did or not I found myself running around 8:15/mile and with the help of the Garmin I was able to keep on track. I don’t remember much of the run other than it was scenic and all around the New Forest. I’d bought five gels, which is the only race I’ve ever used them in and on advice took one every forty-five minutes thereby consuming the 4th at the 3-hour mark. It worked well and when I finished in 3hr40min59, I still had one left.

As with any marathon the running got tough in the final miles. I’d covered the first twenty in 2hr45 and the final 10K in 55mins. It was slippage that cost me perhaps five minutes and had I gone into it better trained maybe I’d have achieved a sub 3hr30 time but I was happy with what I’d achieved. I still am.

Most important to me was I’d done the whole run without stopping or walking – the only one of my four. I started running in the early 1990s when races were still predominantly filled by club runners. The sub-4 marathon was the benchmark for any aspiring runner and while it was accepted you might run out of steam and need to walk at some stage; running all the way was a badge of honour.

Incidentally when I arrived home and checked my emails, I found had entered the half marathon five months before, back in April. I’m not sure how I mixed it up but there’s no doubt from the training that I always intended to do the full 26.2 miles.