This post is the 3rd in a series of six. Other posts can be accessed from the Readables menu tab. So far, in part 1 I discussed how the real Maffetone Method is a holistic system for living but most people are only interested in the low heart-rate training formula. In part 2, I plodded through my experience of nearly six months’ worth of MAF low heart-rate training. Now I look at what’s right and wrong with this as a training system. Let’s get critiquing …

My own experience with MAF training was not very positive and within this post, I’ll explain why. But my aim is not solely to run MAF training down, I don’t see Maffetone as some kind of salesman selling snake oil or a “get quick rich” scheme – he knows about health. As a chiropractor of many years’ experience there are some good things to be learned from his book and there are certainly some athletes who have had success working with him. So let’s begin by seeing what we can gain by understanding his work.

What MAF can teach you

Benefit 1 – Understanding Aerobic and Anaerobic training is very useful

Maffetone explains training can be fuelled in two ways – aerobically and anaerobically. Aerobic uses oxygen and is very efficient, anaerobic works independently of oxygen which causes fuel to burn quicker and creates waste products that limit or fatigue you.

While anaerobic energy enables you to hit your top speeds – after all sprinting uses it extensively, Maffetone explains the detriments of training anaerobically. It increases the acidity of the body, requires more energy and can have major downsides in terms of poor sleep, appetite, weight among other things.

Understanding that too much anaerobic training at the expense of aerobic training is an important concept to grasp and is quantified these days in Stephen Seiler’s 80:20 rule. Perhaps because Seiler’s research only appeared recently, the older MAF low heart-rate training is proposing something closer to a 100:0 ratio.

Benefit 2 – Understand the Aerobic/Anaerobic threshold

Scientists will tell you there is no definable “Threshold” where you cut over from aerobic to anaerobic mechanism. Your exercise is always fuelled by a mixture of both. While this is technically true, the reality to you as a runner, is there are times when it’s clear you’re relying on one type more than the other. Stephen Seiler found research indicating most sub-elite runners are training anaerobically 70% of the time and need to bring this down to 20%.

Benefit 3 – The premise behind lower heart-rate training is right

I remember while running Bournemouth Bay Half Marathon in April 1996, commenting to a chap running alongside me that my heart-rate was averaging 177bpm and he replied “That sounds rather high”. We were only running at about eight and a half minute miles and I went on to finish in 1hr51. This is exactly the sort of heart-rate that people Maffetone met were always training at, and what MAF training is designed to address and bring down. Had I been successful in getting lower heart-rates, I would have seen my half marathon times begin to improve. That’s what MAF low heart-rate training is all about and why the premise is right.

At the other end of the scale, I’ve run at nine minute mile pace with my friend Simon, who is a 2hr34 marathoner and his heart-rate was only 110bpm. That’s the heart-rate of a man who has built his aerobic system and is burning fat.

Somewhere between these two extremes lies the aforementioned threshold between aerobic and anaerobic where you want to do much of your training. MAF suggests this occurs at a heart-rate that is calculated using your age but as I’ll explain later, I don’t. The premise is correct, very low heart-rates e.g. 110bpm are burning fat; heart-rates up in the 180s are burning sugar, or more correctly the glycogen and glucose that is sugar-based. Training somewhere between these two endpoints will lead to effective training.

Benefit 4 – Warm-ups are great

Maffetone devotes a section of the book to getting athletes to spend at least twelve minutes warming up. Genuine warm-ups are one of the most under-rated things in distance running training.

Most people start their runs quickly and then slow down to a pace which feels comfortable. The problem is that by starting fast they activate lots of anaerobic, sugar-burning muscle fibres which are then able to kick in every time they’re needed. This is one of the reason why people say they can’t run slowly. Those anaerobic muscle fibres are the thing that cause high heart-rates.

If you start a run slowly, you only use as many muscle fibres as you need to get the job done and can stay aerobic much more easily. This is reflected in lower heart-rates and focuses the training on building the aerobic system.

Benefit 5 – Low HR training can teach you the feel of Easy runs

Most coaches agree “running your easy runs too fast” is the number one mistake runners make and it’s not even limited to amateur athletes. Even elite athletes can do it and send themselves into a spiral of overtraining and underperformance.

If you pay attention to how easy your low heart-rate training runs feel then you can begin to understand just how easy they need to be. Remember easy is a feeling not a pace.

Benefit 6 – MAF Method would probably help with the “obesity crisis”

While MAF makes no claim on this I found when I built my aerobic base up (using my own method) I stopped being hungry. I still ate carbohydrates but I could return from an 18-mile early Sunday morning run at 8min/mile pace, eat a bagel and banana and then not get hungry until the afternoon. I actually found myself having to schedule meals to avoid missing them! My lifelong desire for cake, crisps and sweets which had been a large part of my diet naturally ebbed away. It returns whenever I start to train more anaerobically.

When you consider there’s a sizeable proportion of the population who don’t do regular exercise, and they get out of breath quickly when they do, it suggests their aerobic systems are underdeveloped. If their aerobic systems are underdeveloped then they’re going anaerobic in even the simplest activities and they’re burning up sugars from the muscles which need to be replaced. This leaves them hungry and prone to eating quick-fix sugary food to sate their appetite.

If people were to develop their aerobic system then they could go about their day-to-day activities without ever needing to dip into anaerobic energy at all. This would give all the benefits Maffetone details around not revving up the central nervous system and getting stressed. It would lead to better fat-burning for fuelling activities and avoid hunger.

My doubts about MAF training

I’m looking here almost exclusively at training to a heart-rate determined by the age-related formula. That’s the part that’s grabbing most people’s attention and they’re promoting as MAF training. (It occurs to me as I write this that I’ve been referring to it as “low heart-rate training” which of course it probably isn’t for anyone in their twenties but allow me that indulgence).

A) The science behind the formula is debateable at best

At its simplest the MAF formula is suggesting that as you get older, you get better at burning fat. But, to my knowledge, there is no known mechanism to suggest all 20-year-olds will burn fat at 160HR, 30-year-olds at 150HR, 40-year-olds at 140HR, 50-year-olds at 130HR and 60-year-olds at 120HR. Even with the small 5-10 beat adjustments these numbers have no scientific basis.

I’m inclined to believe he’s substituted age for experience.

Typically a 50-year-old runner with thirty-plus years of experience will have a bigger aerobic base than a 20-year-old runner and this is why training at lower heart-rates may be better for them. The latter’s youthfulness does give them the ability to engage high levels of muscle which push the heart-rate higher than an older runner who, with the natural decline from ageing, has lost some top-end speed.

While the human body declines with ageing, it is not so abrupt that a forty year-old needs to train at twenty beats lower than a twenty year old. At close to age fifty, I’m running aerobically at 150HR where the formula predicts I shouldn’t run quicker than 130HR.

B) Maffetone defines aerobic exercise as fat-burning and anaerobic as sugar-burning

While this is a good simplification, it’s nothing like the science. It’s accurate to say the anaerobic system is sugar-burning but the aerobic system is a mix of fats and sugars. It’s possible to build an Aerobic system that is burning high levels of sugars – this is a process called Aerobic Glycolysis (also known as Slow Glycolysis) and generally equates to your marathon pace.

In fairness to Maffetone he does hint that some of the aerobic system’s energy will come from sugar – for example on p.23 he shows Mike Pigg running at 127HR as getting 30% of his energy from sugar. It’s when Pigg gets to 153HR that he’s beginning to go 50-50 between fats and sugars.

It’s difficult to get the body to pure fat-burning other than by being careful about what you eat. This is why a significant part of the bigger Maffetone Method (not just low heart-rate training) has you looking at your nutrition and trying a two week no refined carbs regime. But if you change your diet to remove most of the sugars then you don’t need to train to a heart-rate as you only have fats available to burn.

C) Fat-burning is only required for long distance events

Building the aerobic system is important for all distance runners but fat-burning (remember the aerobic system can also be sugar-burning) is only useful for racing events lasting longer than 1 – 1½ hours. That means twenty mile races, marathons and ultras.

Fat-burning can be useful for half marathons but when your times are closer to the top end of the field then you’re unlikely to run out of glycogen stores. If you’re running middle-distance, parkruns or 10Ks fat-burning isn’t going to help your race times.

It can be useful to develop your fat-burning for training runs as this leaves your glycogen stores in tact for harder efforts. This is especially true for cyclists and triathletes who do many more hours of training and therefore find it easier to deplete their glycogen stores (i.e. bonk or “hit the wall”) and these athletes seem to have made up a significant portion of Maffetone’s clientele.

Basically, fat-burning is unnecessary for racing the shorter distances but building a strong aerobic system, mainly based on aerobic glycolysis, is important.

If you’re a young runner training to a high MAF-HR then you aren’t solely working on fat-burning, you’re working on improving aerobic glycolysis. The MAF training will work but not because you’re fat-burning as he suggests.

D) Older runners can struggle with low heart-rate training

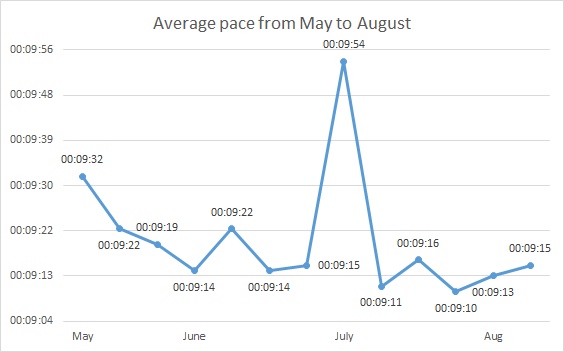

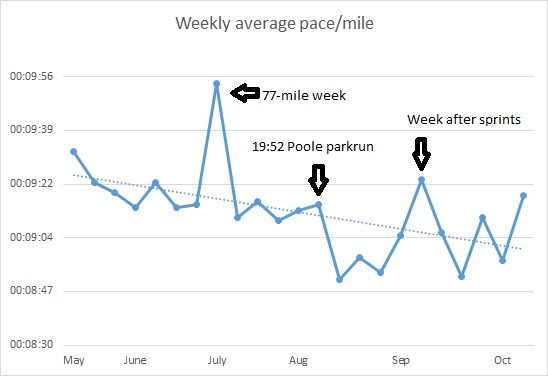

When I was forty-two, I trained to a MAF-HR of 138bpm which usually meant running no faster than 9min/mile. As I’ll show in a future post, my current training has progressed by running at heart-rates in the high 140s and 150s which are far in excess of my MAF-HR.

To progress you have to train at the point just before you start to increase the use of anaerobic energy (reread Benefit #2). This has variously been called the Anaerobic Threshold, Aerobic Threshold and Lactate Threshold among other names. It doesn’t matter what it’s called but it does matter that you’re training at it if you want to get faster.

As she approached age thirty, Paula Radcliffe was setting the world record for the women’s marathon, an event which is run almost exclusively using aerobic energy. She was running at heart-rates in excess of 180 where a MAF-HR would have limited her to 160-165 bpm. Imagine therefore how limiting it can be for the oldest runners expected to train at 120-130 heart-rates but won’t see any improvement if their threshold heart-rate is higher.

E) It’s tough on Fast-Twitch runners

You may have heard of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle which are respectively good for speed and endurance. While slow-twitch is perfect for aerobic exercise, fast-twitch naturally works anaerobically and requires extensive development to improve aerobically. Even then it is less efficient than slow-twitch muscle and can easily switch back to anaerobic mechanism. This is the reason why after a weekend of sprints and drills, my own MAF training went backwards.

Of course, this is why heavily fast-twitch runners are better suited to sprints and shorter distance events. But even a mile world record holder like Peter Snell could run a marathon in under 2hr40 despite sitting down at the side of the road and taking a rest break after the first twenty miles! It’s not impossible to build a good aerobic base with fast-twitch muscle just harder and it’ll usually incur higher heart-rates which makes the MAF age-based formula less appropriate.

Naturally fast-twitch runners will retain FT muscle longer into old age so when you combine this with the previous point (D) you can see why I struggled with MAF training and why others may too.

Note this is why MAF training will likely work very well for slow-twitch runners who naturally run with low heart-rates and actually struggle to get their heart-rates up. They can push harder on all their runs without exceeding MAF-HR (unless they’re Paula Radcliffe) without going particularly anaerobic. But then they don’t particularly need a heart-rate monitor to hold them back.

F) Female runners may struggle with it

The female runners whose training I’ve observed tend to run with higher heart-rates and certainly this was the case for Paula Radcliffe (see last paragraph of point D).

In his book “Better Training for Distance Runners”, Peter Coe states that women tend to have higher heart-rates because their hearts are physiologically smaller and therefore pump less blood with each stroke which is compensated for by beating quicker.

Maffetone makes no distinction in his system for male or female runners or those who have higher maximum heart-rates. He’s very clear that maximum heart-rate don’t matter.

G) MAF training is not a system for training a beginner

It’s likely that if you try to run below a MAF-HR as a beginner runner you will quickly be exceeding it at all but the slowest pace. This could especially be the case if any of the previous three points apply.

At age 47, I got injured and after a three month layoff I resumed training. In my first week I was barely able to run ten minutes per mile without finishing runs at heart-rates in the 160s. I generally took my runs as easy as I could and my parkrun time was under twenty-four minutes after a month but I was rarely running below my MAF-HR. If I had stuck to a MAF-HR, there’s no way I’d have been at that level after a month and running sub-1hr40 half marathons six months later.

H) MAF training says nothing about volumes of training

While the book focuses on the intensity of your runs, it doesn’t give any concrete information about how much training to do; only in broad terms about “less is more”.

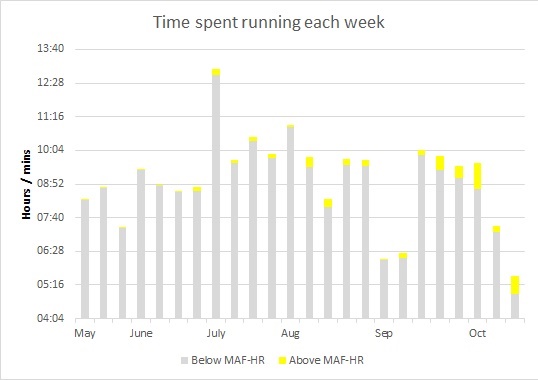

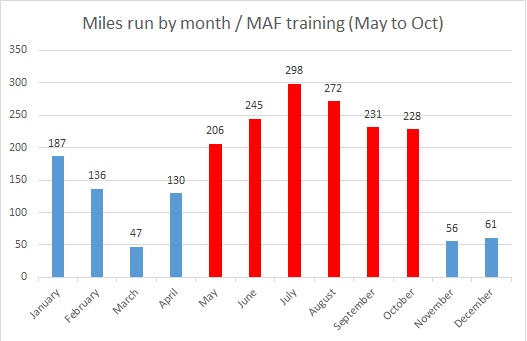

I dived in and did too much relative to my ability with 8-10 hours each week but I’d read elsewhere that low heart-training allows you to do as much you want. It turns out I simply didn’t need to be doing that much training.

How much you should do depend on what your body can take. When you’re beginning, you only need relatively short runs to create a training effect. A couple of hours spread out through the week will have a big effect. I currently train from 5-7 hours each week and get decent benefits from it. My friend Simon, the 2hr34 marathoner trains closer to 10 hours each week.

I) MAF training is not a speed system, it is about creating speed endurance

Although MAF training promises to get you faster, more often than not it’s helping you to race longer distances faster. It’s a subtle distinction. What I mean is that while you might be able to run one mile all-out in eight minutes, MAF training will simply enable you to build the endurance to do a parkrun or 10K at this pace but you won’t necessarily be able to run a single mile faster. That will only happen when you do some speed training. If you only ever do low heart-rate training, you’re eventually going to come up against a brick wall of no improvement.

This is why my first three months of Maffetone training saw no improvement in their average pace but why after I did a parkrun, it picked up – the parkrun acted as a speed session because I went all-out at it and my natural fast-twitch muscle kicked in.

If you never work on your speed side you’re never going to reach your potential. Maffetone does allow for some anaerobic interval workouts but you’ll only know this if you read the book. There’s not much details on these intervals and speed workouts or how they relate to different race distances.

Real world problems with MAF training

I’ve observed many runners who get enthusiastic about MAF low heart-rate training but I struggle to think of anyone who has benefited from its long term possibilities. This isn’t necessarily because MAF training is flawed but because the runners following it, don’t really follow it. Here are the common issues I see.

i) Runners don’t follow MAF training long enough to see the benefits

The aim of the MAF training is to build the aerobic system and this happens by the body improving the aerobic capabilities of slow and fast-twitch muscle. Biologically, muscle fibres start to grow more mitochondria which improve the use of oxygen; meanwhile the capillary network that supplies oxygen from the arteries to the muscle fibres becomes more extensive. It is these changes that allow cells to extract and use more oxygen from each beat of the heart hence why it then needs to beat less frequently to deliver the same oxygen levels.

The process for growing new mitochondria and capillaries takes six weeks so this is the minimum timeframe you should be focused on MAF training if you’re to get its benefits. But it’s not necessarily a one-off hit as you’ll usually be growing these on a rolling basis. So while the training you do in week 3 is reinforcing the growth that started a few weeks ago, it is also initiating further growth that will be realised in week 9. This is why the elites can stay in a base period for months.

However if you start racing or doing heavy speed workouts during your MAF training period, which is what I tend to have seen, the full benefits may not be realised. Often there’ll be a small improvement but not as good as they might have been had they committed. I’ve even seen suggestion that capillary beds can be destroyed if too much speedwork is done but I’m not sure how true this is.

The people I see raving about MAF training on Youtube, the web or Strava never seem to follow the system for a period of months like I did. It’s a fad for them. Invariably they follow it for some of their runs each week but then throw in a race or workout regularly. This is contrary to the idea of MAF training which, I believe, is supposed to be a continuous process.

They might as well go follow a marathon training plan and get the same benefits from high mileage and minimal speedwork

ii) Runners don’t actually stay below the calculated heart-rate

When I MAF trained I was dedicated to staying below the MAF-HR. I don’t see the same zealousness from other runners. Most of those I’ve seen trying it are capable of running decent times e.g. half-marathon in 1hr25 but to stay below their MAF-HR might require them to go back to nine minute miling aka “running too slow”. So they tend to slow their runs down to about eight minute miles and be content if their heart-rate averages the MAF-HR. Occasionally they will stop, walk or go up hills slowly but mostly they jog along doing an approximation of MAF training that doesn’t bear close scrutiny.

iii) Runners don’t use a decent heart-rate monitor

Until a decade ago all heart-rate monitors were chest straps which were usually accurate. You could get inaccuracy at the start of runs which was usually solved by giving it a lick before putting it on but otherwise they tended to be accurate.

The new generation of wrist-based heart-rate monitors are highly unreliable in their accuracy despite the manufacturers’ claims and any inaccuracy is usually put on the runner for not wearing the watch correctly. I’ve seen countless examples where runners have heart-rates in the 180s while jogging and then when they start doing fast intervals the heart-rate drops to the 140s. That’s a physical impossibility. The wrist-based monitors often lock onto a runner’s cadence but there may be other reasons behind their inaccuracy.

Whatever the reason I would only trust a chest strap heart-rate monitor from the current technology available. It may improve and there may be some which are already reliable so if you choose to go wrist-based, test it before you rely on it. And do that test under a variety of conditions, not just sitting on your sofa or walking to the local shop.

iv) Runners don’t do the warm-up

Runners who try MAF training almost always start their runs fast, only slowing down after a minute as the anaerobic boost runs out and they start to puff. The problem is they’ve then engaged more muscle than they can run aerobically with, this makes it much harder to stay under MAF-HR.

To compensate for increased anaerobic energy usage, the body invokes lactic clearance therefore that’s what they’re training rather than signalling to the body a need to adapt aerobically. Once lactate clearance kicks in, it’s possible to be running anaerobically and still see lower heart-rates.

A secondary issue of starting runs without a warm-up is heart-rate monitors can read inaccurately at the beginning of runs and this causes big headaches if the heart-rate monitor is constantly beeping say you’re running too fast. It often takes 8-10 minutes to settle down and has disrupted your rhythm if you’re trying to stay below a certain heart-rate. I used to worry on my MAF runs if my heart-rate was up in the 140s early on not knowing whether it was me running too fast or the monitor reading wrong.

As I explained earlier, Maffetone recommends doing a fifteen minute warm-up which helps to avoid these issues. Many of the MAF training advocates don’t have the patience or knowledge to do this.

The BIG flaw to MAF training

Heart-rate monitors don’t show the levels of lactate in the blood.

As I wrote back in Point D (and will reproduce here to save you scrolling back up): To progress you have to train at the point just before you start to increase the use of anaerobic energy. This has variously been called the Anaerobic Threshold, Aerobic Threshold and Lactate Threshold among other names. It doesn’t matter what it’s called but it does matter that you’re training at it if you want to get faster.

Most people understand the principle of Threshold training so I won’t go into depth about it. What I will point out is while there are various ways of identifying what the heart-rate at threshold is, only Maffetone suggests it is related to age. And quite simply – it isn’t.

It can vary drastically depending on your training. I have seen myself running at Threshold heart-rates of 127bpm after doing excessive amounts of speedwork yet two months later it’s up at 150bpm. There was no relationship between my age and Threshold heart-rate in those numbers and there won’t be in anyone else – other than by coincidence.

In well-trained runners the Threshold heart-rate is more consistent. Mine is usually somewhere around 152-153bpm when I’m running well. Coach Peter Coe said lab testing shows it’s usually around 150bpm in male runners but higher in women. Mike Pigg, who I mentioned earlier appears to be around 153bpm. I would be very careful about using a generic value like this to specifically define the Threshold but with experience you may be able to define where your own starts.

There are very few, if any, elite runners these days who train to heart-rate. If they do it’s usually to ensure their recovery runs are slow enough. If they are doing workouts by heart-rate, it’s likely they’ve derived their numbers either by taking lactate samples or by using heart-rates experienced in races. An age-based formula won’t identify it.

In my opinion, if you really want to train to heart-rate, you’re better off going with a catch-all number of 150 (or 160-170 for a woman) and see how your body reacts to it. I would aim to run recovery runs at least fifteen beats lower than this but not get too tied into staying exactly below or on the numbers. I’d look to do a warm-up that takes at least ten minutes to get close to my target heart-rate but I’d let my body guide me on how it wants to run. If I began to go over the target heart-rate then I wouldn’t be too concerned by a few beats but I would look to ease off and get back under target. I would aim to run the 150HR rate efforts no more than three times per week with the low heart-rate recovery runs on the other days.

That’s if I was going to train to heart-rate which I don’t.

Summing up MAF training

The idea of training to build an aerobic base is a good one for anyone involved in endurance sports. Whether this needs to be fat-burning or sugar-burning depends on the distance(s) you intend to race.

But the fundamental concept of using an age-related formula to decide on what heart-rate to train at is high flawed. There is no proven mechanism that reliably explains why a 40-year-old runner should train twenty beats lower than a 20-year-old runner.

Remember Phil Maffetone was a health practitioner who treated all sorts of endurance athletes so being a running coach was never his speciality. What the MAF method does well is to (re)build a healthy aerobic system. This allows runners to peak their training with anaerobic training for better race times, but MAF training itself is not a system for building top end speed. You will only go as fast in races as your top end speed allows. If you spend months creating a super-efficient aerobic system, it opens up the space to access speed at the top. If you never do speedwork you won’t be any faster over short distances but you will improve over longer ones.

While many of his clients found great success from following his methods, the success stories he details are of already-elite athletes in their respective long distance events. They were already fast and well-developed, MAF training just took them the final steps of their journey. For example, Mark Allen was placing in the top 5 of the Hawaii Ironman before he met Maffetone. He became a six-time champion when he improved his aerobic system because fat-burning is crucial in an event lasting over eight hours.

What Maffetone showed these athletes is how to build the aerobic system which is the foundation of endurance. That is half of running. The other half is the anaerobic system which helps create speed. Following the Maffetone approach as a complete running system is like listening to researchers who tell you that you can get faster by building VO2max through High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT). It’s only half the job. Good running coaches already understand how to combine these two halves of aerobic and anaerobic training to create endurance and speed to maximise the potential of a runner. It’s often self-coached runners who have fixated on one half or the other who profit when they introduce the other type of training.

If you go through Maffetone’s Big Book you will find all the athletes he gives specific details for are elite (i.e. they already have top end speed) and they are under thirty which gives them a higher MAF-HR to work with. It’s for this reason I repeat my belief that the Maffetone formula is a blunt instrument which could as effectively be replaced by a catch-all heart-rate limit of 150 beats per minute for male runners and perhaps 10-20 beats higher for women. The specific value you use would likely need to be individualised and decided upon once you’ve got used to your own typical values.

There are better ways to train than MAF training to be the best runner you can. These involve mixing periods of short intervals, long intervals, continuous runs, long runs and easy runs at a variety of paces to develop both speed and endurance.

Update – since publishing this, I wrote a further post proving my point about there being better ways to train. In it, I detail how I trained regularly breaking my proposed MAF-HR, often training to one the equivalent of someone twenty years younger than me yet still made progress. Read Part 4 – The myth of MAF here.

After pondering what encourages runners to give MAF training a try, I wrote Part 5 – Why MAF why, which tries to explain their motivations. If you’re considering giving it a go maybe you’ll recognise yourself in some of the descriptions!

Recently I published Part 6 – When you need MAF which looks at the circumstances that might indicate a block of endurance training focused on lower heart-rates might be useful. But, as I point out in Part 4, low doesn’t mean age-related.