This post is the 4th in a series of six. Other posts can be accessed from the Readables menu tab.

When I tried MAF training I ran for 5+ months, logged 200+ hours of training where only 4½ hours was spent above a heart-rate of 138bpm. This heart-rate was determined using Maffetone’s age-related formula that I can see no scientific basis to explain. I can’t say I got any notable benefit from the training as I could run a 21-min parkrun before I started and, at the end of it I was running 20:39. In the midst of it, I did run 19:52 but regressed after doing some sprints and drills on a coaching course.

The training itself was demoralizingly slow and I was always fearful of the heart-rate monitor beeping at me to slow down because I’d exceeded the maximum heart-rate. I said I’d never train with it again because it was so unenjoyable and because there are better ways to train.

Today I’m going to prove there are better ways to train to get the same benefits.

Six months of non-MAF training

Let’s roll back to November 29th at the end of last year when I ran my standard Sunday long run in 1:39:26. It’s an average pace of 8:31/mile and my heart was pumping away at an average of 148 beats per minute. Six months later, May 30th, I ran it again, a minute slower, but my heart-rate was now only 131bpm. That’s a drop of 17 beats and an indicator I’d improved my aerobic system.

Regular readers will know I’ve spent the intervening six months training for 800m following a plan from one of Jack Daniels’ books. Although I know much about coaching and how to train I’ve never tried middle distance before, so I decided to see how one of the world’s best coaches approaches it and see what I could learn.

As I’ve documented in monthly updates – January, February, March, April – I logged 40-45 miles per week with a mix of easy runs, long runs, intervals and threshold runs. The training got tough in the depths of winter but I got through it. I ran every day and while I got tight at times, I never got ill or injured. By April I was ready to test out my new found fitness and was highly surprised when I only achieved a 3-second improvement!

Nonetheless a few days after a second 800m time trial I ran my long run a minute faster (1:38:38) than in December and was now averaging a heart-rate of 140 – eight beats lower. So I’d done nothing like Maffetone training and improved by his measures.

I suspected the poor time trial results were due to a lack of endurance and embarked on six consecutive weeks of nearly fifty miles through April and May as I documented in my May 800m update. When I ran another 800m time trial it was still about the same at 2:53, a five second improvement over six months ago, but the rest of my running was feeling easier. My easy runs had sped up but more notably I broke 1hr30 on the long run in training. An improvement of ten minutes for a nearly twelve mile run.

What would MAF suggest?

Seven years ago at age forty-two, when I tried my MAF training experiment, I calculated a MAF-HR of 138. But actually, given I was coming off an illness, I should have taken ten beats off and used 128bpm which would have made things even harder and certainly slower.

Being older, Maffetone would suggest I now train to a lower heart-rate than I did last time around. At forty-nine this gives an initial MAF-HR of 131 but I’ve been running daily since late 2019 without issue. According to MAF you need to have trained for two years without issue to be allowed to add a further five beats, but for this comparison I’m going to do it anyway and analyse my recent training against a MAF-HR at 136bpm. This may sound like a cheat but if I used the lower figure, the stats would skew even more against MAF training.

If you’re wondering why I’m calculating my current MAF-HR when I said I was never going to use MAF training again, it’s purely to analyse the recent training I did and show I improved despite not following any of the low heart-rate training that MAF recommends.

Recent training

What follows is a look at my training for the six weeks after my mid-April time trial. There are one or two miles missing where I was coaching or giving a Personal Training session, as well as a couple of days where I didn’t wear my heart-rate monitor but the bulk of the training is shown.

The general format of each week:

- Eight mile Steady runs on Tuesdays and Fridays with a ½-mile warm-up / cooldown aiming to run at my threshold.

- On Sundays the long run, usually at the crack of dawn, again pushing it along and throwing in some strides along the way.

- The other four days of the week I aimed for a forty minute recovery run.

With six consecutive 50-mile weeks, this block of training totalled 300+ miles and 42 hours.

Yet when you break down all this running, twice as much time was spent running in excess of my MAF-HR (136) as below it. (Note: there is a small issue with the software I used to total the Above-Below durations because it double-counts heart-rates of 136-137 into both categories. The actual figures were 28 hours above MAF-HR, 14hr45 below it but only 41hr50 total run time).

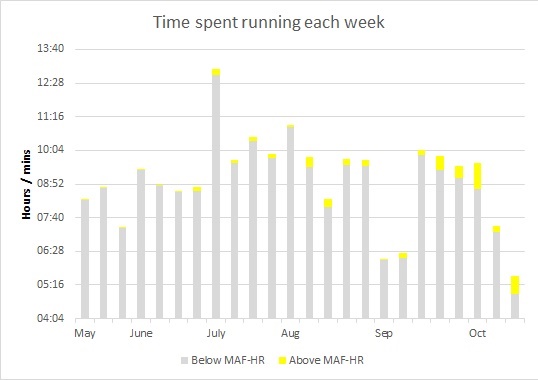

You can see in the graph below the length of each run in time and the proportion of it spent above or below MAF-HR. The yellow is the time spent exceeding it and accounts for 65% of running time. Almost every day I was exceeding MAF-HR for some of the run – that can’t be good according to Maffetone.

Now take a look at the graph of 2014’s MAF training where I only exceeded the MAF-HR for 2% of the time. You can barely see any yellow in the early weeks and it doesn’t increase a whole lot. In the graph above, I often spent more time above MAF-HR in a single run than I did in a week then.

It’s not even close. It’s very clear I was constantly breaking the MAF-HR in my recent training and not just by one or two beats as happened back in 2014, but by large margins.

Here’s a graph of the time I spent in excess of 150HR on those runs. You can see I was regularly running for over 45-mins with heart-rates on the Steady and Long runs that were nowhere close to MAF-HR. I was effectively training to the MAF-HR of someone over twenty years younger than me.

What’s amazing is I accumulated twelve hours of running at over 150HR which isn’t much less than the nearly fifteen hours I ran below my recommended MAF-HR of 136. Yet somehow I got exceedingly better results than when I trained to MAF-HR in 2014.

Getting faster

Not only was I seeing improved heart-rates, my effort runs were improving too.

The November run was my fastest time on the long run course at 1:39:26 and with the 800m training this had reduced to 1:34:03 by March. On 2nd May I reduced it to 1:32:55 then on May 23rd took it down further to 1:29:15. The average heart-rate on this final run was 149 which is only one beat higher than when I was running it in late November. Then my fastest single mile was ripping along down Gravel Hill at 7:52, by late May I was sub-7 with a 6:58.

On the Steady runs I only have one comparator. Back on November. I ran a local 7 ½ mile course round Merley which took 58min52 at an average pace of 7:54/mile and the fastest mile was 7:33. In mid-May, during a spell of high winds I decided against going to the beach and opted to run the local route in 20mph winds. The run came in two minutes quicker at a pace of 7:38/mile with the fastest mile now at 7:08 along with a couple more showing in at 7:18 and 7:21. At the beach, I’ve begun to see miles in the 7:05-10 range. There’s no doubt I’m speeding up and if I were racing longer distances I’d certainly see better times.

Better ways to train

I’ve loved the past six months of training for all the reasons I hated the MAF training. I got to run fast, sometimes I even got to sprint as fast as I could. I rarely looked at my heart-rate while I was running and I certainly didn’t have the heart-rate monitor beeping at me to slow down. The variety of paces and training sessions kept me interested as well as nervously excited on occasions.

I haven’t cracked the 800m yet but I’m confident training is going in the right direction to get there. I’ve seen improvement and I’m running faster than six months ago with heart-rates at slower speeds being lower. That’s an indication the body is improving its fat-burning capability. I’ve been sleeping deeper, got leaner, faster and remained healthy and injury free which are the sorts of reasons Maffetone puts forward for following his method.

The premise of MAF training is that to improve fat-burning you have to run at low heart-rates and stop eating carbs. I did neither of those. Across six months I regularly hit higher heart-rates and I never restricted my diet or stopped eating carbs – if anything I’ve eaten more during the winter months with two bags of Doritos each week and regular cakes from the bakery. Yet I proved it’s possible to achieve the promised benefits of MAF training despite regularly breaking the heart-rate that it suggests a man of my age should use.

None of this was achieved by sticking to a heart-rate calculated from my age and is why I put no stock in MAF training as a system in itself. I believe there may be applications for it in certain circumstances but not general training.

I’d love to hear people’s comments and questions about this block of training and my MAF training review. All reasonable scepticism or thoughts are welcome!

I’m a 53 y/o guy. About to start my 4th week of MAF training and I was already wondering that if there’re adaptations occuring at the lowest range of my my MAF mhr (122) then surely those adaptations must still occur at higher numbers. I don’t know about 150 bpm, as it still sounds a bit too high for me (never been a fast runner) but I believe raising just ever so slightly my MAF mhr, maybe to 127-130 bpm, could help boost my pace to 12 min/mile or so, which for me would be a treat! It’s still early days, and I want to see what kind of improvements, if any, await for me in 2 months time. I really enjoyed reading about your experience with the Maffetone method.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment Eola – I’m always interested to hear and learn from others’ experiences.

I recommend taking it through to the six week mark before you make any changes as this is the time for building a cycle of mitochondria and capillaries. If you don’t see any significant improvement soon after that, you’ll want to change tack. Obviously I don’t know what your fitness / genetics / health / times / goals are like, but it’s usually safe to do one or two harder efforts each week – you need these if you are ever to get faster.

If you haven’t already read part 3 of my MAF series (Good, Bad and Ugly) it’s packed with my thoughts about where MAF works and doesn’t. You may see something in there which chimes in with your experience. It’s a long read so grab a cuppa if you decide to!

Good luck with your training and please, do come back and let me know how it’s evolving.

LikeLike

Hey Hugh,

Thanks for the solid analysis and experiences shared with your MAF training. The best one I could find so far.

I also have some issues with the MAF heart rate being statically defined based upon age. Being 50 years of age I could not see any significant progress with my MAF HR of 135. Lab tests only showed a decrease in my resting lactate levels up to my aerobic threshold which is currently 6 bpm above my MAF (141). Even training a couple of weeks up to my aerobic threshold (131 to 141 bpm as suggested by Phil Maffetone) showed no improvement in terms of increased speed. As I could not find any lactate test curves that would put the thresholds in relation to MAF I was forced to incrementally experiment with upping my training heart rate. I meanwhile ended up with a new heart rate ceiling of 148 to 150 at which I train around 20% of my weekly mileage (Seiler approach). The remaining 80% I stick with a training HR at or below my actual aerobic threshold. Since I started following this training pattern I see tremendous improvements of my running speed. I am still experimenting but I guess I have now got the gist about what may work for me in a long term (e.g. like upping my mileage @ 148 bpm or experimenting with a few heart beats more). Anyway, I became a strong believer in training at “low“ intensity in order to prevent injuries. If it gets too low though, it is just getting you nowhere due to the lack of training stimulus.

Cheers,

Stefan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for details of your experience Stefan and confirmation of what I’ve written.

We’re the same age and using a similar upper training heart-rate – I reckon mine to be around 152-153 and can do a well-paced Steady run without exceeding this. As I wrote in part 3, this seems to be the standard HR for most men; I tend to coach people towards that if they have a decent heart-rate monitor.

What you’ll likely find if you up the mileage (and I have no idea of your current routine) is it’s hard to reach the top-end aerobic heart-rate day-in, day-out. This is because you’re burning high levels of carbs and the stores will inevitably need restocking which forces you into slower days. Plus muscle fatigue may also knock some fibres out of use and make it hard to run fast enough to get the HR up.

Good luck. Please check back in with your experiences in the future.

LikeLike

Thanks for all these articles. I have been looking into the MAF method, but somehow the language used in the original book sounded immediately rather unscientific (almost cultish) to me, and it seemed to me that the basically good central idea of running most of your weekly runs at a low HR had been made rather obscure by a lot of other stuff with no sound evidence. Your articles have done a good job of crystallizing my concerns into a coherent whole.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Chris – glad I could help you sift through. I think Maf’s Big Book is an interesting read and there is some useful stuff in there. Given his chiropractic background, his attitude is more holistic which doesn’t gel with science’s reductionist approach. I did a Sports Science degree myself but have come to realise the science of VO2max, LT, running economy or heart-rate training zones can’t be used in isolation to become a better runner either. There is much more goes into running than just that which can be measured!

LikeLike

All elites do a whole stack of training at MAF or below; lots of people (it seems yourself included) like to think they are the outlier who can train at 20 beats higher (or whatever) and still progress.

LikeLike

All elites may well “do a whole stack of training at MAF or below” but that is a consequence of elites being young and therefore having a MAF-HR in the 150s. It’s obviously much easier to stay below MAF when the number is high.

As I wrote here I trained at higher HRs and made progress, so I’m not sure why you’re attacking me.

The key is I also made sure to put in frequent recovery days which happen to be closer to my MAF-HR. That’s all Maffetone wanted the injured people who came to him to do, balance their training and not go hard every day.

LikeLike

No ‘attack’ apologies if it came over that way. A lot of aerobic progress (regardless of whether you want to call it MAF approach or not) comes from efforts well under, MAF 1800-age limit. The elites I mentioned do a lot of work far under MAF also. It’s common for elite cyclists for example to do a lot of riding under 125bpm (similar for elite runners). Yeah you can make progress going above but it comes with a big risk of breakdown, burnout, illness and injury. Personally I think training at the heart rates that you did when much younger is asking for trouble (although the decline is likely less for lifelong athletes. Each to their own 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks James. Cyclists are interesting because the bike does the weight-bearing and therefore heart-rates are naturally lower. If I recall rightly, if you do a Lactate Threshold test on a cyclist, runner and swimmer the heart-rate for each will differ with a runner’s being the highest. So again it’s much harder (but not impossible) for cyclists to get their HRs above MAF.

My general view is that decent athletes do not run around with their HR monitor dictating their training other than perhaps on their recovery days where they have number (which is not MAF) to keep it as recovery.

LikeLike

I think the best part of a MAF approach is acknowledging the impact of the rest of your life on athletic performance (a lot of other programs only pay lip service to this I feel), yeah 10bpm above MAF is still giving a an excellent aerobic training effect (for most) however its also more stressful and most people already have a lot of stress in their lives. 80/20 is often touted as ideal but this can be oversimplified for an average athlete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ultimately, the major flaw in MAF is that, despite saying that it looks at athletes individually, it is based on the same flawed age formula that is wrong for 35% of people and wrong by double digits for 10%. Jim Ryun had a MHR of 230 when he was 21 years old. MAF would have limited him to 159, or 69% of his MHR.

On the other end, Hal Higdon reports a MHR 25 lower than the age formula suggests. So, when he was 45, his MHR was 150. The MAF rate for him would be 135, or 90% of his MHR, a rate that pretty much everyone agrees is anaerobic.

If one in three are outliers, and one in ten are major outliers, wouldn’t it make a lot more sense use something like HRR to determine the best heart rate training zones?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent points Steve – superbly backed up with good examples

LikeLike

Good read about your journey training in MAF Method and doing your own training work adjust to what your body can handle and adapt.

LikeLiked by 1 person