Let’s play a game …

Here are the times from my last ten 5K parkruns – 23:31 … 23:16 … 23:06 … 23:27 … 22:54 … 23:06 … 23:37 … 23:37 … 22:50 … 23:16.

What’s your prediction for my next 5K time?

If you said somewhere around 23 minutes – well done. Maybe you went for 22:45 to give me a booost – I wouldn’t be against that.

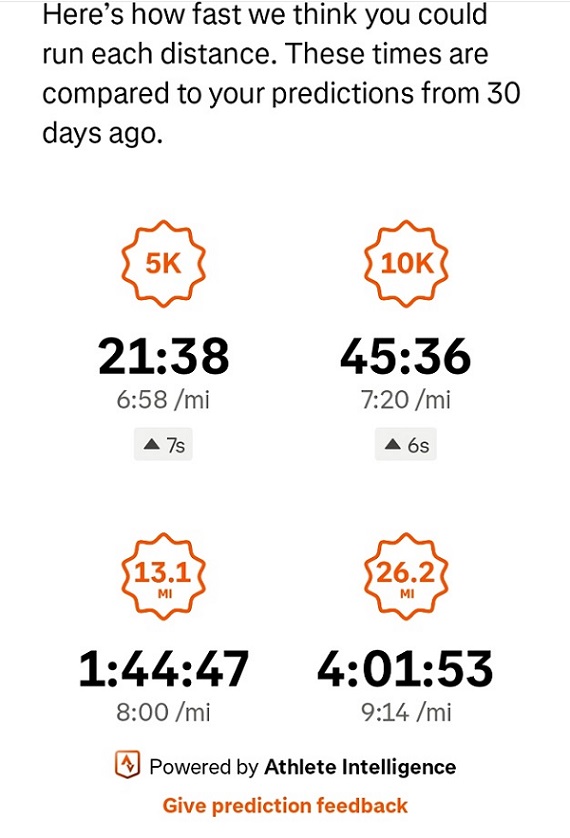

But would you have said 21:38? I certainly wouldn’t.

Yet Strava does.

Strava recently gave me a month’s free premium membership and they seem to have embraced AI with gusto. Among the features is its willingness to Predict Race Times. Despite having the perfect info available – weekly 5K – Strava is reckoning I can run over a minute faster. Clearly I can’t unless I change my training and then their prediction will probably change.

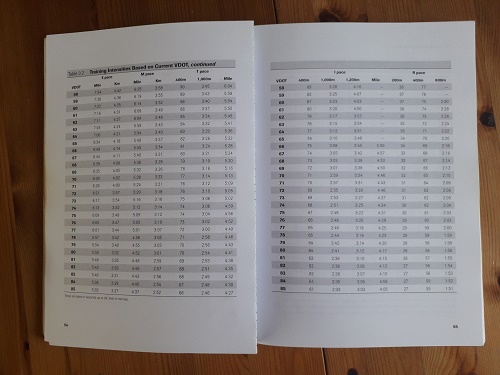

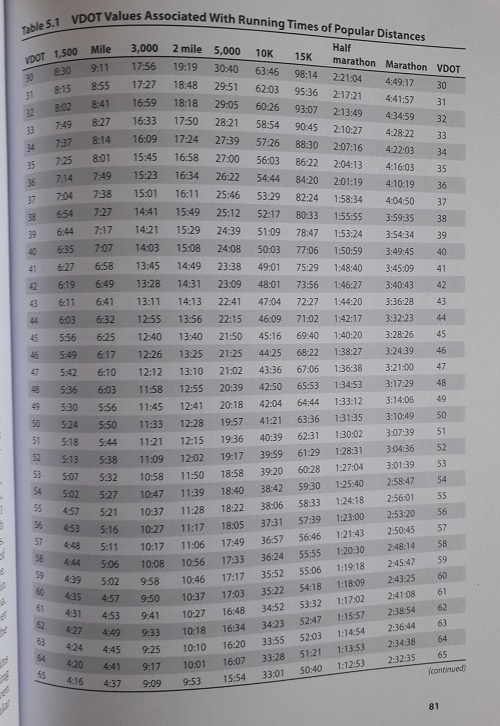

Last month I ran a 6:48 mile to celebrate Banister’s Mile. I know that’s not fast but I’ve been concentrated on building strength in the gym and working on very short distances – I expected my aerobic base to erode and it did. But if I take a look at Jack Daniels’ VDOT tables he estimates a 6:49 mile equates to a 23:09 5K which is relatively close to the 22:54 I ran at parkrun a few days later. It’s not perfect but it’s not frustrating me into thinking I can run over a minute quicker than I’m capable.

Looking at the other predictions – the 10K of 45:36 is essentially double this Season’s Best for 5K – so that isn’t going to happen. I reckon half marathon at 1hr45 is reasonable and JackD’s VDOT suggests 1hr46 although I wouldn’t be surprised to see myself slip to about 1hr50 given I haven’t run over five miles in almost a year.

VDOT predicts a 3hr40 marathon which is very unlikely and Strava’s 4hr time is probably closer to what I’d achieve. But again, if I entered a marathon tomorrow, I doubt I’d come close to either time because I’d wilt and be walking from fifteen miles. If I trained properly for the distance, I’d feel more confident about VDOT’s prediction; the Strava prediction would then be too slow but it would probably update itself with the training. But if it has to keep revising times as the training changes then that seems a little disingenuous – rather like the person who tells you “Oh I knew that” after you read out the answer to the trivia question they had just given up on.

With each run you upload there is Athlete Intelligence feedback to tell you about the run or workout you’ve just done. For example, this is what it stated for the run I’d just done at time of writing …

It’s a bit bland.

And it’s only half correct.

It correctly managed to figure out I do the same route most days (“maintaining consistent 3-mile distance”) and it correctly figured out whether this was faster or slower than usual (“at a slower pace”) but the last sentence (“while exploring different intensity zones”) is complete rubbish. I went out at an easy, recovery pace and maintained the same intensity throughout. What did happen is that I ran up some hills which caused me to run slower (but using the same effort/intensity) and down some hills which caused me to run faster (still using the same effort/intensity) and under some trees which will have messed around with the GPS.

As for the first couple of words (“Recovery run”) Strava had enough intelligence to take this from the title of my run! When I changed the title to “Steady” the summary changed likewise. It really wasn’t rocket science to figure that out although when I changed the title back to “Recovered” with a deliberate -ED ending it went back to calling it a “recovery run” and when I tried “Interval session” it ignored that.

I decided to look at what it had to say about previous days. For example here’s an interval session …

This is a pretty good description of what I’d done but what does this final bit (“and a challenging mixed-pace run.”) say or mean? They’re just empty words describing what it thinks I’ve done but not what it really was – warm-up, intervals with rest breaks, warmdown. Technically it’s a mixed-pace run but not like going out and doing a proper fartlek session where you mix the paces up.

I looked back to a speed development session where I sprinted four efforts of 5 seconds followed by further efforts lasting 10seconds, 15seconds and 25 seconds. Between the efforts I walked back to where I started, stood around and had long rests. It ended up taking about 25mins to do seven efforts. Here’s what Strava had to say …

It got the first line correct but not much else. There really were no varied effort levels, it was max effort from start to finish on the sprints. And I’m guessing it thinks this was “significantly slower” because the 0.7 mile of total sprinting and walking comes out at 12+ min/mile. Compared to a recovery run then this is significantly slower but of course it is – the aim and structure of the session is totally different.

Here’ s what it said about a 23:16 parkrun …

Well that’s strange, I didn’t do any intervals – I ran a 10min warmup, a 5K parkrun, a 5min warmdown. And the parkrun was 25secs slower than my Season’s Best the week before so it can’t have been a “route personal record”.

What can I say? It all sounds like unintelligent garbage to me.

Of course I don’t help Strava much by having an old Garmin watch which doesn’t feature many of the latest variables and I stopped wearing a heart-rate monitor months ago. But I run just about every day and upload my data to Strava – there’s almost ten year’s worth of data about my running for Strava to crunch. And yet I don’t find it’s telling me anything useful.

That said, I haven’t investigated their Runna coaching service – why would I? I coach myself and know how to train others for results. If you need an individual plan then I can help you but equally standard plans have been available in magazines and on the internet for years – and while I’d expect Runna to adapt depending on how your training is going (which is what I do with the runners I coach), I’m not sure how good it is at that. I also question its ability to motivate – I’ve known a few people try to follow coaching plans given to them by their Garmin watches but have yet to hear of anyone who succeeds or even completes the programme.

At the moment AI feels rather like “cut & paste” software. It feels like the gym assessment I used to get where it would state “BMI is the relationship between your height and weight, with your value of [Insert value] kg/m2 shown above in Illustration 1. Your value places you in the [Insert rating] category. However, it is worth noting that BMI doesn’t take into account factors such as muscle and lean body mass.” Lots of description with just a couple of personalised bits of information added in.

I remember how these five or six page documents initially impressed me but after retesting, I came to realise that they were just padding out my numbers with waffle. Eventually all I did was look at the graphs and numbers. I suppose AI has an advantage because it can rephrase the same information in different ways thereby giving the impression for longer that it has something important to say.

I’m sure AI will improve in coming years and when that happens I’ll probably be out of a job. But one of the reasons AI will continue to improve is that it continues to scour the internet. I receive a significant number of hits from AI tools which are reading my blogs and trying to make sense of them.

In the meantime if you want personalised coaching from a real human being – this far I’ve not used AI in my blogs or plans – then click here to Contact me.