It’s thirty years since I ran my first half marathon. It was in Portsmouth and had 1,600+ runners taking part. Earlier this week I went up into the loft and dug out my box of old race packs. To look through it is to be amazed by how the culture around running has changed. It’s also quite amazing to see how badly I trained for the race.

The day was Sunday March 10th 1996 putting it six weeks ahead of that year’s London Marathon and therefore it was perfect for anyone taking part in the longer distance. For those doing so it provided a chance to find out where their fitness is at; practice any race strategies and time enough to recover with some further training thrown in. We should note I was not doing London that year!

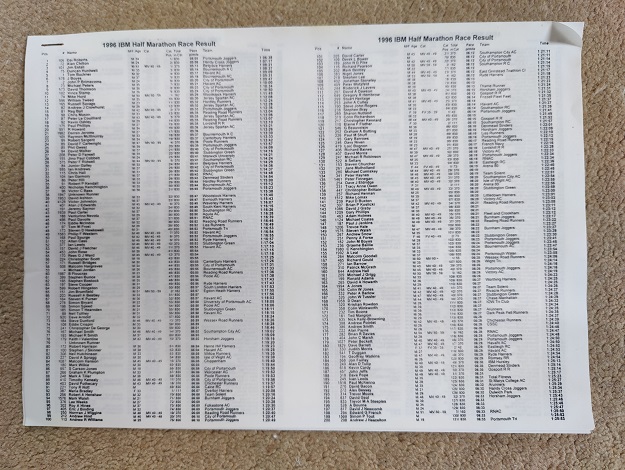

These days races take place every weekend; there are even races on the same day as London – a day which was once sacred to runners. This proliferation of races has taken place over the past fifteen years as running has become more egalitarian and diverse with professional race companies capitalising on the gaps which were once available in the club racing calendar. Clubs used to organise the vast majority of races and looking at the results leaflet from my half that’s very clear.

To get that I probably supplied a stamped Self-Addressed Envelope and received the results three weeks later. Today we expect the results with hours of the race – for example last Saturday my parkrun time came through at 10:41am which isn’t bad considering the tailwalker finished just before 10am!

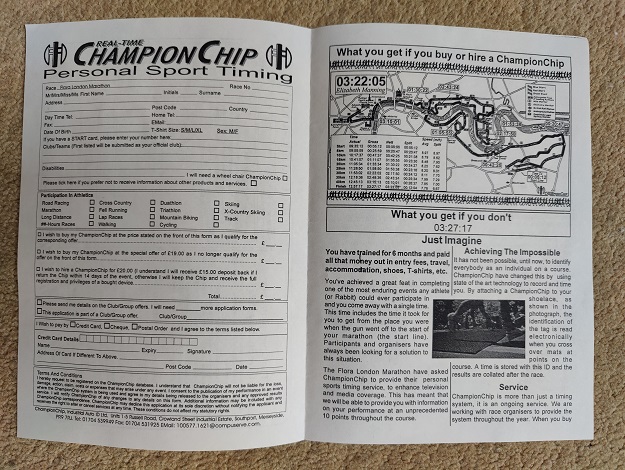

These were also the days without chip timing. Or at least they almost weren’t because in my race pack there’s a leaflet where you could BUY your own Champion Chip for the London Marathon for £18 or hire one for £20 which also required a £15 deposit to be paid to ensure you returned it within a fortnight. The application form is very detailed and full of marketing info. It’s quite incredible to consider that the first attempts to get chip timing into races would have involved everybody buying and owning their own chips whereas now they are supplied by professional timing companies and while a chip may be attached to your shoelaces and reused; they are often simply disposable on the back of race numbers.

As for the results themselves what’s obvious from a glance is how many of the runners belonged to a club. Of the top one hundred finishers; only ten are without a club and there’s only another twenty-two in the next hundred. Even I entered as a club runner although I didn’t consider myself one. There was a running club at work and they got me to put it on the form as there was the possibility of my placing counting towards a team prize while getting me a cheaper entry fee. Realistically given my lack of distance running ability I don’t think there was ever a chance of my time being quick enough to count but that was the deal we made.

The other clear thing about the results is how quick everyone is. Seven runners breaking 1hr10; the 200th runner is under 1hr26 and the average time is under 1hr43. At the other end of the field, I can’t tell you the time of the last finisher because the slowest recorded time is 2:16:33 and then the last one hundred runners who follow are given the same time. Race cut-offs were a lot stricter then.

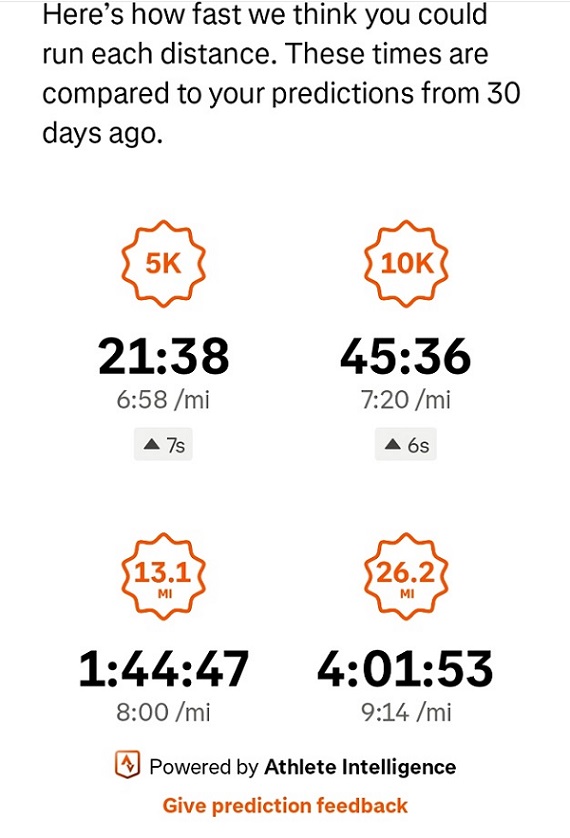

My run came in at 1:51:36 which by today’s standards would be considered a decent time for a first half marathon especially when you consider how poor my training was but we’ll look at that lower down!

For now let’s compare the results from 1996 to last year’s Bournemouth Half which attracted 5,300+ runners yet only has forty-one runners breaking 1hr20. The median average time is almost twenty minutes slower at 2hr03 and while a 1hr51 half marathon would have put me just outside the top quarter in Bournemouth, in Portsmouth I was 65% of the way down the results sheet.

While those last hundred runners in Portsmouth represent about 5% of the field, at Bournemouth which is admittedly a course with more hills, 30% of the field clocked that time or slower. It seems many more people now feel more comfortable with attempting a half marathon than they did then.

Training

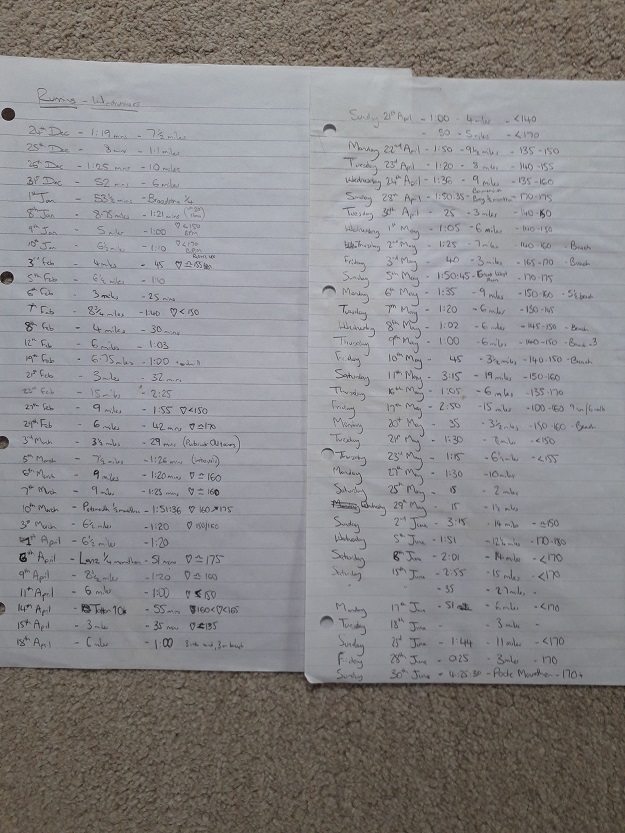

At Christmas 1995 I started logging my runs. While I used a computer at work, I didn’t have one at home so they were handwritten on paper. There’s a heading indicating this was specifically the mileage I did in the fresh new pair of Nike Windrunner II shoes I’d bought.

I guess I’d been running at various times during 1995 – I often went to the beach after work and ran three, six or nine miles along the prom. I also had a 3 mile loop from my house and another measuring 4.5miles. I figured out the distance of those by driving round the course in my car. I couldn’t take my car on the prom so I estimated the distance using a piece of string in the local mapbook and convert the distance based on the scale. Bear in mind this was long before GPS became a thing or there were route plotting services on the internet.

Looking at my training I’d summarise it as being rubbish. Rather than have you squint at the photo of my handwritten notes I’ve put the relevant info into a table. I suspect around Christmas time I went running fairly frequently because there was nothing else to do. The gym would have been closed for a few days and our volleyball league was having a break. Quite why I did six miles the day before a New Year’s Day quarter marathon I’m not sure but I recall not wanting to do the race due to a cracking headache from our New Year’s Eve night out. My friend Christian dragged me off the sofa, gave me a cuppa and made me go to the run. There was a bit of running the following week and then nothing until February.

| Dec 1995 | ||

| 24th | 7.5miles | 1hr19 |

| 25th | 1.1miles | 8mins |

| 26th | 10miles | 1hr25 |

| 31st | 6miles | 52mins |

| Jan 1996 | ||

| 1st | Broadstone Quarter Marathon | 53:30 |

| 8th | 8.75 miles | 1hr21 |

| 9th | 5 miles | 1hr (HR <150bpm) |

| 10th | 6.5miles | 1hr10 (HR<170bpm) |

| Feb 1996 | ||

| 3rd | 4 miles | 45mins (HR < 155bpm) |

| 5th (5 weeks to go) | 6.5 miles | 1hr10 |

| 6th | 3 miles | 25mins |

| 7th | 8.75miles | 1hr40 (HR<150bpm) |

| 8th | 4 miles | 30mins |

| 12th (4 weeks to go) | 6 miles | 1hr03 |

| 19th (3 weeks to go) | 6.75 miles | 1hr (treadmill) |

| 21st | 3 miles | 32mins |

| 23rd | 15 miles | 2hr25 |

| 27th (2 weeks to go) | 9 miles | 1hr55 (HR <150bpm) |

| 29th | 6 miles | 42mins (HR 170bpm) |

| March 1996 | ||

| 3rd | 3.5 miles | 29mins |

| 5th (Final week) | 7.5 miles | 1hr26 (intervals) |

| 6th | 9 miles | 1hr20 (HR 160bpm) |

| 7th | 9 miles | 1hr25 (HR 160bpm |

| 10th | Portsmouth 1/2 Marathon | 1hr51:36 (HR 160-175) |

It’s quite possible I didn’t enter the half marathon until late January hence no motivation to run. I also recall it was a cold winter to the extent that my hands wouldn’t warm up at the start of runs even while I wore two pairs.

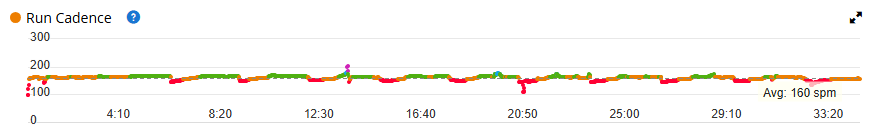

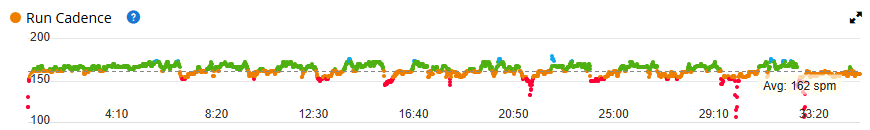

Training seems to have begun in earnest with five weeks to go. I now realise that’s nowhere long enough to build mitochondria or capillaries for a better aerobic system which is why the runs where I have recorded a heart-rate show it to be as high as the 170s.

Once I actually began training I was running 3-4 times per week which isn’t bad although the week beginning 12th doesn’t seem like I ran much. I think that was the weekend I went to visit my friend Gary who was living in Cologne, Germany so I was catching flights on the Friday and Sunday and being a tourist in between.

What is somewhat galling to look at is what I did in the final days leading up to the race. Three runs of 7.5 – 9miles and including some interval training. There is nothing you can do in that final week to get fitter. You need to keep running to signal to the body that you haven’t given up but there’s also no point in doing too much or too fast when you want the legs to be fresh to run.

Race day

I recall very little about the race other than I got up early on the Sunday, it was a sunny morning and I was able to get to Portsmouth in about 45mins without any trouble. Like any other first time half marathoner I would have felt a little overawed by the experience although I had done 10K races some years before.

What I most remember about the race is somewhere around the ten mile mark there was a woman perhaps 20-30yards ahead of me. She was older than me probably in her fifties. Yet as much as I tried I couldn’t close the gap. As a very fit twentysomething who played all manner of sports this unsettled me. I felt almost indignant that this woman, who I judged to be nowhere near as fit or healthy as me should be uncatchable. But as much as it bothered me, it also gave me a great moment of insight and that’s why I remember it. The simple fact is I knew nothing about this woman. For all I know she might have been the marathon world record holder thirty years prior. Realistically she wasn’t but the point stands, I knew nothing about who she is, who she had been or how much she had trained for this race so what did it matter that I couldn’t catch her. It was an immature judgement based on looks and personal preconceptions but it triggered insight that has stayed with me ever since about how we can’t compare ourselves to other people.

Today I now realise why I couldn’t catch her. My lack of decent training meant my aerobic system hadn’t been developed and I was being limited by lactate build-up. I’m sure I managed to find a finishing sprint for the line but other than a few seconds quicker my time wasn’t going to be significantly faster that day than it was. That was proven in the other three half marathons I ran that summer where they each came in around the same time.

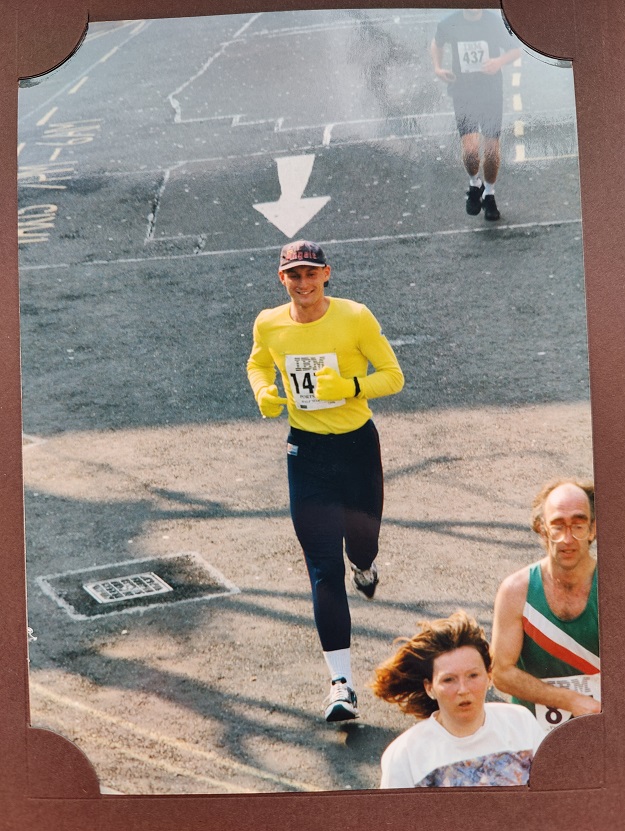

The Photo

And so we need to discuss that race photo. I love that the big arrow painted on the road is perfectly aligned to point at me, the photographer did well there. I look in horror at the heelstrike I’m perpetrating and horror at what I’m wearing.

In fairness the preceding winter had been cold so I’m not entirely surprised I’ve gone with warmer clothing and I don’t recall feeling hot on the day. I used to sweat profusely on runs even if I was wearing just shorts and a t-shirt. But my word, it does seem a little overdressed with long sleeve top, Ron Hill leggings, gloves and California Angels baseball cap. The cap actually served an important purpose it was keeping a Boston Redsox bandana in place on my head because without that the sweat poured into my eyes. I’m not really a baseball fan but I’d picked those items up on holidays in America and while I never usually wore them, they became an important part of my running kit. To this day I still run with a bandana.

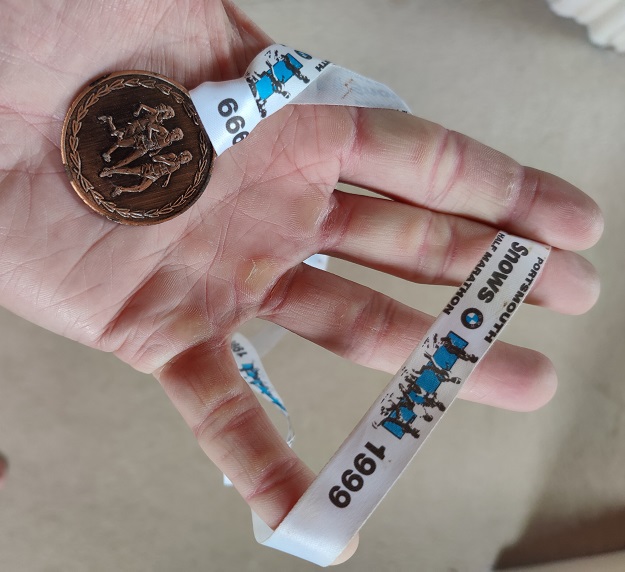

The Medal

I said at the beginning times have changed. I can’t find the race medal but I’m fairly sure it’ll have been similar to the one from when I ran the race three years later. And I think the difference with today will be obvious. It’s barely bigger than a coin. If modern races offered that I suspect the participants would be up in arms. The only reason they’d post it on social medal would be to complain about it!

My box of old race packs has many medals like this. I’m sure it’s significantly easier to get custom designed medals cheaply created for races these days whereas they were uninspired and samey then. But I recall that as the 90s turned into the Noughties runners became less enamoured with these medals. With races mostly populated by club runners who were entering perhaps a race per month for years on end, they simply didn’t need another when they had a drawer full of them already. Different times.

The final picture below is of my race pack. There’s the Information Pack which you’d now download for yourself off the website; the Results booklets I received three weeks later; my Race Number with a rectangle missing from the corner because they tore that off to marry up the race times to positions and the chip timing offer. All of it neatly presented on a massive IBM sponsored white bin bag which was for putting my kit in and taking to bag collection.