I used to coach a triathlete who had decided to run a marathon. In our discussions he told me that one of the tough parts of a triathlon is the transition from cycling to running. You get off the bike and then when you start to run, the legs feel like rubber and they take a couple of minutes to adjust. I later heard people say cycling is quad-dominant whereas running is glute-dominant. While nice descriptors it didn’t really explain what was going on.

The glutes are the muscles in your backside or rear, the quads are in your thighs. You can find many articles written about runners who have lazy glutes due to sitting at a desk all day and suggesting exercises to activate them. Along the way I’ve tried many of these, both for strengthening and activation without much success. As a kid, I cycled everywhere so my thighs grew big and muscular and no doubt that led me to be quad-dominant in powering all the exercise I did.

If you’re a cyclist, or like me were one, this post is going to help you understand how it could be holding you back from achieving your running potential. If you’re a runner, like I’ve been for over a decade, you’ll probably benefit from understanding how using your glutes to their full extent might help your running. I’ll explain the difference between quad and glute dominant exercising; showing why runners should be aiming to get their glutes active and providing some ideas on how to do this.

Cycling is quad-dominant

Here is a cyclist sitting in a recommended position for setting up the saddle. Opinions vary as to the correct method but they are all small variations of what you can see – the leg almost, but not quite, straight when the pedal crank is at the bottom. The yellow lines indicate parts of the bike – the saddle position and the pedal cranks. When they’re vertical the cyclist will have one foot at the highest and the other at the lowest point of the pedal stroke. We’re particularly interested in the lower point because that is the furthest the foot gets away.

Most of us have been on a bike and we know that each stroke is powered by pushing down on the pedal. When the foot reaches the bottom, the other foot has reached the top and it then takes over pushing down to keep the pedals turning. In essence the cyclist is always pushing down on the pedal to power the bike forward. There is also some debate as to whether cyclists should pull on the upstroke to assist. Even so, all this pushing down, and any pulling up, is due to the quad muscles in the thighs – along with some assistance from the hamstrings and calves.

What doesn’t contribute to the stroke (very much) are the glute muscles sitting on the saddle. There may be a contribution but it’s minimal because the pedals limit how high and low the thighs can move and therefore how much effect the glutes have. You can see the thighs are about 45 degrees apart and as you will see the glutes don’t move much.

Running is glute-dominant

Now let’s look at a world class runner – David Rudisha. I examined his stride length in a previous article where I estimated it to be 2.45m. You can see in the picture below his legs are about 90 degrees apart. So already his glutes are moving through a greater range of motion than the cyclist’s.

His knees don’t come up as high as the cyclist when they come forward. A runner with good form allows the knee lift to occur naturally through elastic energy rather than a conscious lifting of the thighs. This elastic energy is created by the hip flexors on the front side stretching as the leg goes backwards. When the ‘backside’ work has been done, just like an elastic band snapping tight, the hip flexors pull the leg forward.

We also see David Rudisha is extending his leg behind him to the point where only his toes are still in contact with the ground. His back leg is straight from hip to ankle as it transfers force to the ground. His ankle is still a little flexed but having looked at multiple pictures and video, it doesn’t appear Rudisha can fully straighten at the ankle which would be better. The key point to notice is that his leg is extending behind his body which is due to a powerful hip extension. To run forward, he has pushed the ground away behind him.

Running and cycling side by side

If we now compare Rudisha to the cyclist, but rotate the latter so his torso is upright, we see a massive difference between them.

It’s clear from this picture that the legs of the cyclist are always in front of him. There may be some pelvic tilt in his seating to achieve a better aerodynamic position but it’s not enough to be relevant. The position of the saddle, the pedals and cranks ensure his thighs and feet only move in a limited range – the equivalent of 2 – 3:30pm on a clock face. By comparison, Rudisha’s legs are working from about 4:30 – 7pm. The ranges of motion don’t even overlap.

In the cyclist’s rotated position, it’s easier to see how their thighs and knees will piston up and down in front of them. In the normal orientation we see the pedal being pushed down, here perhaps we can think of it being pushed away from the body. This push is achieved by the thigh muscles straightening the knee until it almost locks out. It’s similar to how rowers power each stroke by straightening their legs. This is why cycling is considered a thigh-dominant activity. Of course, dominant doesn’t mean only; so there can be contribution from other muscle groups – just not as much.

Glutes power the stride

Let’s now see why running is glute-dominant with another look at David Rudisha. In this picture he is still airborne with his leg having come forward as far as it will during this stride. Although it’s not easy to see – his lead foot hasn’t even touched the ground yet. He is about to start using his glutes to continue running fast!

As the yellow arrows show his leg will swing backwards with the foot hitting the ground just ahead of his body. He will continue to propel his leg backwards and his foot will momentarily be stationary on the ground as his body passes over it, just like a pole vaulter arcs over the planted pole. As best possible, his leg will remain straight all the way through to the toe-off. Typically the quicker the running speed, the stiffer the landing leg tends to be.

He will attempt to maximise pushing the ground away behind him by fully extending his rear leg until only his toes are in contact with the ground as we saw in the earlier photo. When that point is reached the leg will naturally fold up behind him and pass forward under the body due to the elastic energy created by the stretched hip flexors. The runner doesn’t need to trying to do anything to bring the leg forward or lift the knee.

The glutes

Swinging the leg backwards is powered by the glute muscles which are a group of three muscles in the buttock area. In recent years the Kim Kardashians of the influencer world have attracted attention to them by getting implants and doing exercises specifically intended to make them larger.

In running we’re interested in using the glutes to extend the hip. Again this is the sort of phrase that doesn’t mean much without thought, and it’s possibly easier to understand it by thinking about what happens when you stand up. The legs move from being at 90 degrees in front of you to straightened below you. Extension of a joint is straightening it. Hip extension is straightening at the hip – it increases the angle on the front side.

In this picture of a glute muscle we can see them crossing the back of the hip and pelvis. If the person were now to stand we can imagine that the glute muscles would ball up to give the Kardashian look – just as a biceps muscle gets bigger when it is flexed. This is why runners, especially sprinters want big, strong glute muscles.

When runners flex the glute muscles the leg moves backwards and the front of their hip straightens. When the foot hits the ground, the continued action of contracting the glutes causes the leg to pass below the torso and then behind. Of course we rarely feel this as contracting our glutes, it feels more like pushing the ground behind.

The issue is people usually have no reason to flex the glutes that far back and if we’re not practiced on it, we don’t do it as runners. When we stand we only contract the glute as much as necessary to bring ourselves to an upright position. We only need our knees and feet to be directly below us. When we walk we move the leg a little behind us but do it slowly and not too far. Then we often take our next step by falling forward and rolling onto the heel of the lead foot.

As Rudisha shows there is a range of motion where using the glutes deliberately will create a full and powerful hip extension so that the leg and foot move further behind. Unfortunately this is not what quad-dominant runners or cyclists with their strong thighs and poor glute activation do when they run.

How cyclists often run

We saw in previous pictures, the typical cycling position doesn’t even bring the cyclist’s feet to the ground if they are turned upright. Obviously this isn’t what happens in real life when a cyclist tries to run.

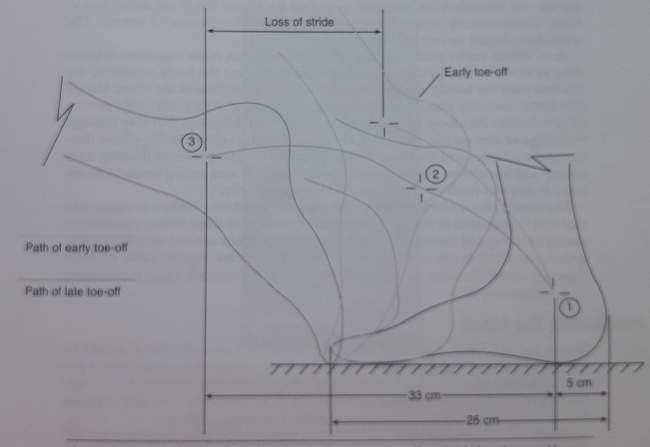

While cyclists are very good at pushing the foot to the ground using the thighs and exerting push, they often don’t learn to extend the leg back past the vertical. Instead almost as soon as the foot has landed they feel the stride is complete and pick the knee back up. Where the runner’s leg comes forward using elastic energy, the cyclist uses their strong thigh muscles and hip flexors to lift the knee ready for the next stride.

Statistically this gives them the sort of measures their sportswatch likes – high cadence and short ground contact time – so they think they’re doing the right thing. What they lose though is stride length as the foot doesn’t push them as far forwards as it could with a longer range of motion. As Steve Magness writes in The Science of Running “Often, the mistake is made in trying to get the foot off the ground as quickly as possible, but remember it is only when the foot is on the ground that force is transferred to the ground. While having a short ground contact time is beneficial, it should be a result of transferring force faster and not of getting quicker with the foot.” (p.307)

Strengthening glutes

I’m a big believer that once you start using the correct muscles to do the job they quickly strengthen themselves up with regular running. Even so there are a variety of initial strengthening exercises you can try which may help. These include step-ups, one-legged deadlifts, hip thrusts or frog-legged bridges. As starter exercises for getting more strength into the glutes and supporting muscles they are good options but they don’t take you past straight hips and therefore don’t mimic that extra bit of power we’re looking for.

Donkey kicks may be the best exercise for really squeezing the glutes but other than by adding ankle weights it’s not possible to create resistance for adding strength and power. If you lie on your back and do hip thrusts you can add resistance especially if you progress to doing them on a one-legged, on a step or with a weight across your hips.

But having strong muscles doesn’t guarantee using them during runs. If your movement patterns are wrong, it doesn’t matter how strong the muscle is they won’t help out. A simple example of this principle is when people try to pick up a heavy object. Health and safety advises them to bend their knees and use their legs. More often than not people simply bend over at the waist and strain their back. It doesn’t matter how strong their legs are if they don’t use the correct technique.

I haven’t described these exercises in detail but a quick internet search will turn up a myriad of articles or Youtube videos demonstrating them.

Activating glutes

To begin to get the movement correct you need activation exercises. A simple one is to imagine pushing a shopping trolley or pushchair. Basically to imagine there is something that will block your legs from swinging ahead of you which forces you to push the foot or leg backwards to create the propulsion to go forwards.

You can also try standing with your back against a wall and then stepping away from it. Feel the back of the leg and heel push off the wall using the muscles around the hips.

Walking lunges can be a good exercise for creating the hip flexor stretch and getting the glutes to work. They also work as a good balance and coordination exercise. You really have to focus on getting the glutes to work.

These sort of activation exercises may work at giving you the feeling you’re looking for but personally I never managed to carry them over into my running.

Toeing off

While David Rudisha doesn’t appear able to full point his toes he is certainly pushing his foot and toes as far back as possible. The following compilation of pictures of Seb Coe show how great his form was in this area.

Practicing toeing off has been the exercise I found most useful. When your foot hits the ground put pressure through your big toe and push your foot all the backwards until the leg is fully extended behind you and you are up on your toes. NB This is not running on your toes but pivoting up onto them when the leg is at its furthest point back.

Peter Coe, coach and father of Seb, highlights in Better Training for Distance Runners” that a fully straightened ankle which has pivoted over will leave the ground late and create extra stride length over that of a runner who either keeps their foot flat on the floor or with the heel barely lifted off. This pivoting can adds over the length of the runner’s foot to each stride.

To achieve strong ankles and good rear leg extension, Arthur Lydiard the great running coach of the 1960s, had three strengthening exercises – steep hill running, hill bounding and hill springing – which he scheduled as a four week phase prior to speedwork. He is quoted in Healthy Intelligent Training as saying “Increase in speed comes from flicking of the ankles. If you want speed, you don’t need to be built like a body-builder. You need to be like a ballet dancer, with springy and bouncy ankles” (p.118). However Steve Magness writes “Unlike what many suggest, do not try to get any extra propulsion out of pushing off with the toes consciously.” (p. 307)

There’s clearly a contradiction between what these two coaches are proposing but there is no doubt a fully extended leg with pointed toes is critical to achieving speed and stride length. My own interpretation is that by pushing the foot through for the full stride, you naturally lever up onto the tip of the shoe and your toes. Knowing that Lydiard’s hill strengthening came at the end of months of aerobic distance training, his exercises were there to help runners get used to this action again. Once you’ve got strong ankles and good technique you probably won’t even notice it happening and there will be no flick. I think the key to Magness’ statement is about not consciously flicking the ankle, as there runners who try to get a bit extra by doing this but are actually creating inefficiency in the mechanics.

Whether Lydiard or Magness is right about ‘the flick’ doesn’t matter for most runners as it’s a “1% improvement” whereas many runners haven’t mastered the gross movement of pushing with their glutes to end up toeing off which is where the big gains will be made. Initially if you aren’t pivoting up to toe-off, you aren’t getting the most out of your glutes and will need to go through a conscious phase of deliberately toeing off to achieve this.

Lydiard’s hill exercises also work on getting that rear leg extension we’re seeing in Coe and Rudisha. I’ve found this is best achieved by ensuring the back of the knee straightens, that it feels almost as if it’s being pushed back beyond what is physically possible.

Ultimately even your running shoes are built to enable you to toe-off. Every pair has the sole extending forward, up over the front of the shoe yet few runners actually wear this down. When you look at how far it turns up you realise how much encouragement you have to do this.

Summing up

The best runners in the world power their running by using their glutes. The glute muscles swing the leg backwards from its further point out in front of the body to the furthest point behind. Elite runners push the ground away behind them and then allow elastic energy to bring the leg forward again for the next step. Each time their foot hits the ground they are pushing themselves on to maintain speed or accelerate just as a skateboarder keeps the deck rolling by occasionally pawing the ground with their foot.

This contrasts to the average runner, or those who are thigh-dominant, who stopping pushing with their glutes when their foot hits the ground, allowing their momentum to carry them over it as they pick the knee back up. In doing this they decelerate while the foot is on the ground, miss out on stride length and the free elastic energy available for bringing the leg forwards. As Matt Fitzgerald states in The Cutting Edge Runner “when you retract your leg properly, your foot feels as though it grips the ground rather than lands on it. From this point all you have to do is keep thrusting backwards, and you will have effectively minimised any stance phase and the deceleration that comes with it.” (p.152)

Making changes is never easy and if you start using muscles that have never been engaged before, they will have some catching up to do. Like a slower runner trying to keep up with a faster pack, they’ll be left fatigued and sore until they have gained the fitness to be part of the group. If necessary back off the pace and distance of your runs, take extra days rest until you begin to feel adapted. Once the correct muscles are active they will start to work for you, the new form will increasingly become second nature and the muscles and tendons will strengthen for themselves as you get faster or try more demanding sessions.

References

- Coe, P. & Martin, D. (1997) Better Training for Distance Runners.

- Fitzgerald, M. (2005) Runner’s World The Cutting Edge Runner.

- Livingstone, K. (2009) Healthy Intelligent Training.

- Magness, S. (2014) The Science of Running.