This post is the 5th in a series of six. Other posts can be accessed from the Readables menu tab.

My previous posts on MAF training are among the most popular I’ve written. Recently I’ve been wondering WHY people keep raving about this method before going quiet on it. It seems like every three or four months there’s someone on Strava or Youtube giving it a go. That I get so many people reading my posts about it is an indication they’re researching it.

Although my experience of Maffetone training was relatively recent, my first experience of low heart-rate training dates back to 1995 using the method in John Douillard’s “Body, Mind and Sport” book. I trained to a heart-rate max of 130bpm for a few months and got nowhere. I came back to it on at least three more occasions in the next decade and a half, still no success. I’ve been trying to remember back to when I first picked up Douillard’s book and what enticed me to give his method a try. While he’s not MAF, the premise is the same – build an aerobic base to get faster using low heart-rate training.

1) Grand promises

When I first read the Douillard book I was seduced by the grand promises it made. The story of Warren Wechsler, a 38-year-old guy who easily ran a 2hr53 marathon within eighteen months of starting the programme and could run six minute miles at heart-rates below 130bpm. Or the high school girl sprinting the last half mile of a cross-country race with her heart-rate maxing at only 140bpm. There was other stuff in the book about getting “into the zone” which tempted me and it all sounded great.

While MAF is never quite as brazen as this, his method also uses testimonials to make grand promises. Here’s a story straight out of his Big Book of Endurance Training and Racing (p.93-94):

Marianne Dickerson was a 23-year-old marathon runner who’d won the silver medal at the 1983 World Championships in a time of 2hr31. She struggled in the following year with a lower back injury until meeting Maffetone. Using the aerobic heart-rate he calculated for her, she found she couldn’t run a mile in under eleven minutes. Over the next eight weeks she changed her diet and kept her training to MAF-HR. She picks up the story “Each week, I noticed my pace became quicker as I was able to run faster within my aerobic limits. After eight weeks of base building, he had me enter a 10K race. I was shocked at how easy the race felt. And my finish time was a personal record of 33:02. Miraculous, I thought, given that a mere eight weeks ago, I could barely run a mile under eleven minutes aerobically and now I was running 6.2 miles at an average pace of 5:18/mile.”

Wow! Who doesn’t want to be running 10K races in thirty-three minutes off a couple of months’ training?

2) Endurance not speed

MAF training is a method that will get you running faster. But what does the word “faster” really mean? When you hear faster, you imagine your parkrun going from thirty minutes to twenty minutes or even quicker. (Fill in whatever a major improvement is for your level). After all, this is the hope which the Marianne Dickerson story is giving you. Except, this isn’t really what MAF training can do for you.

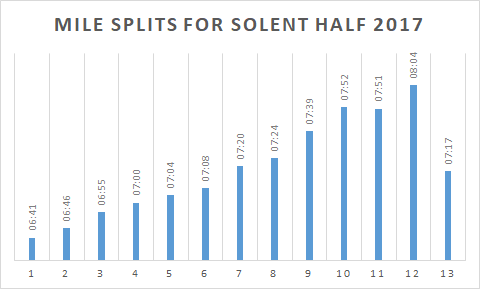

The actual benefit of MAF training is that it will build endurance – which is being able to hold onto a pace for longer. Let’s say your thirty minute parkrun has kilometre splits beginning at 5:30 and slows down by fifteen seconds each subsequent kilometre thus 5:45, 6:00, 6:15, 6:30. All MAF training will enable you to do is run every kilometre at 5:30 pace and therefore reduce your time to 27:30.

It’s not a lie or incorrect to refer to this as helping you get faster because your parkrun has improved and many would be happy with knocking two and a half minutes off. The problem is continuing with MAF training from there isn’t going to help you get any faster because it won’t add any speed i.e. your fastest kilometre will continue to be around 5:30/km.

To add speed you need to do some interval work or hills and these require you to exceed your MAF-HR which, by definition, is no longer MAF training. If you don’t do the speedwork, you’ll be running around to a limited heart-rate for months and seeing no further improvements.

The reason it worked for Marianne Dickerson is she already had her top speed in place and simply needed to refresh the endurance to get back to running 10K races quickly in a matter of months.

3) Simplicity

The simplicity of the age-related formula is a big temptation. It all sounds so easy – “All you have to do is take your age away from 180 to get your MAF heart-rate then avoid going over that number when you run”. It couldn’t be easier. People like things which are easy.

When I first bought a heart-rate monitor it came with an instruction guide to setting zones. 60-79% for aerobic, 80-90% hard workout, 90-100% hard anaerobic or some such. But you needed to know your maximum heart-rate and do some mathematics to set those zones. Then you needed to structure your weekly training to train within the appropriate zones and it was all beginning to get complex and need some thought which is one reason I never did it.

The encouraging simplicity of MAF is you just go out and do every run using the same MAF-HR.

4) Science and technology

The technology of using a heart-rate monitor suggests this is science and therefore it must work.

The reality, as I stated in my The Good, the Bad and The Ugly post is there is no science behind MAF’s formula and the heart-rate monitor can’t identify when you’re going aerobic or anaerobic to help you train effectively.

There is no science behind MAF’s age-related formula, only coincidence.

5) MAF training gives people who train too hard a break.

It’s a revelation to many people how easy an easy run should really be. I reckon many people who take up MAF training find it gives them a chance to have a break from their usual training regime. Amateur runners are notorious for pushing sessions too hard, week-in week-out, so when they discover the formula with all its promises, and find out how easy the runs feel it’s a revelation.

6) It avoids coaches and planning

Many runners have a routine or follow the training of the people they run with. When they’re not getting faster, they’re looking for a quick fix (as MAF promises) and don’t want to plan training sessions or ask for help. The simplicity of MAF training avoids both these things.

7) “It’s going to take a while to see results”

Many MAF trialists start off patiently because they’ve been told it takes a while to see results. This is both true and false. If your endurance training is working, you should see some kind of change within weeks. When I’ve gone back to base training, I start to see or feel some kind of improvement within two to four weeks. Training begins to feel easier, my legs get their spring back, heart-rates on similar runs can go up (“yes up!”) or down, you might begin to see better pace at the end of longer runs. These things begin happening within a matter of weeks if you’re getting it right.

On the other hand, if you’re an established runner building your endurance base from scratch, it will take a while for it to impact your races. There’s probably a big gap between your aerobic pace and your race pace. Arthur Lydiard stated it takes three years to see a marked improvement, but you will see an improvement in the first year and a greater one in the second but it’s later that you begin to see the major benefits.

8) Get rich quick

Like a pyramid investment scheme or multilevel marketing sales, you only hear from the people saying how great it is in the beginning. This encourages others into the fad. When they’re starting out on their get-rich-quick scheme they’re enthusiastic and motivated until they realise it’s not working and slink off quietly into the sunset.

There are rarely dissenting voices who say “I tried this and it didn’t work”. Even then, outside of my own posts, I’ve never seen anyone lay out what they did in their training, detail the ineffectiveness of MAF training and give solid explanations for why it didn’t work.

There’s many people talking about MAF training and what it promises but rarely do you hear from those same people when they’ve given up on it.

NB This isn’t to say well-executed endurance training is a get-rich-quick scheme, it’s not. I honestly believe Phil Maffetone was able to help athletes improve their endurance and times using his methods. I just don’t believe those methods are as simple as the age-related formula has people believing.

Why do they give up?

They get bored of jogging around at low heart-rate numbers doing the same thing every day and waiting for results. Ironically the simplicity of the system becomes its Achilles Heel as lack of variety leads to boredom. For most runners, a month of training is a long time and if they haven’t seen improvement by then, they start to lose interest (and rightly so in my opinion). If they have a race coming up, it takes priority and they go back into speedwork or workout mode.

For some people, the low heart-rate number has them jogging at excruciatingly slow places. There are issues of ego and embarrassment about being someone who usually clips along at seven minute mile paces having to slow down to barely quicker than walking pace. They start to fudge the numbers either stating the formula must be wrong because they have a high maximum or allowing themselves to regularly go over the limit as long as the average is lower than their MAF-HR. If they don’t see quick results, they bail on the method.

Ultimately the main reason runners give up is because it doesn’t deliver the grand promises. I’ve never heard of anyone successfully using MAF training outside of the books. Maybe there is someone for whom it works but I’ve not met them.

There is now a sixth post about MAF training which looks at what circumstances might lead indicate you need to rethink your approach to training.

If you’ve given MAF training a go – please comment and let me know of your experiences – success or failure. Why did you give it a try? How long did you try it? What caused you to give up on it?