Have you heard of Ian Stewart? It’s a popular Scottish name and I used to work with one but I’m asking about the runner who was one of Britain’s talents in the 1970s claiming a bronze medal in the 5,000m at the Munich Olympics. Athletics Weekly recently ran this article detailing his top 30 races.

What struck me was this quote: “First’s first and second is nowhere as far as I’m concerned. This country’s full of good losers. It’s bloody good winners we want.” It brings to mind famous quotes by Liverpool’s Bill Shankly “Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that” or the misquote of Vince Lombardi, head coach of the Green Bay Packers, with “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing”.

It’s an attitude that was prevalent as I was growing up in the 1970s and 80s, even into the early 2000s but one you rarely hear uttered these days. Maybe it’s because we’ve been spoiled with success in athletics, swimming, cycling, rowing, tennis in recent years; whereas for many years championships or medals were rare.

Through my early twenties I fell firmly into Stewart’s camp believing only in the importance of winning and the pointlessness of placing. I first began to understand this could be wrong while watching the Atlanta Olympics where Britain only won one gold medal. “Being a good loser” was never more apparent than in the men’s 400 metres when Roger Black trailed in behind Michael Johnson. Whatever Black did that day he was never going to beat Johnson, the world record holder at 200m and 400m, unless injury or disqualification occurred. Roger Black did the best he could and made sure he won the silver medal. I’m sure he would have preferred gold but there was no disgrace in getting silver that day.

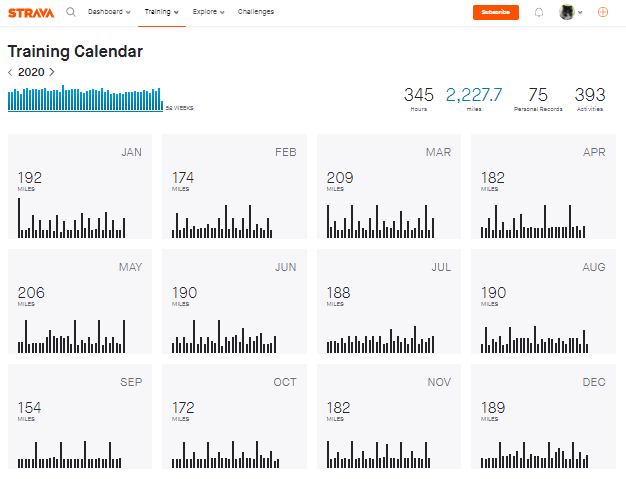

It’s incisive to ask “If winning means so much why not find situations where it’s guaranteed?”. Try racing your 8-year-old and see how important the win is then. On the other hand, try letting your 8-year-old win easily and they’ll be quick to say “You weren’t trying”. Against a mismatched opponent, it becomes obvious winning means nothing to all but the hyper-competitive. You will see people who go looking for guaranteed wins – witness the segment hunters on Strava or those who enter races with small fields or where the winning time was slow last year.

On the only occasion (so far) where I’ve been crowned “First Finisher” at parkrun, I recorded the slowest winning time of the 200+ occasions Moors Valley parkrun has been run. The best club runners were tucked up in bed on a day forecast to have 50mph winds, resting up for a Dorset Road Race League race the next day. But I never turned up that day looking to win, my intention had been to go for a recovery run!

While it was nice to be first, the week before Andy was fastest, the week after it was Tracy. Meanwhile there were another thousand people around the world who were fastest at their respective parkruns. My success was short-lived but for six years, Mo Farah was the undisputed champion at the Olympics and World Championships over both 5,000 and 10,000 metres but eventually someone surpassed him. Being undisputed champion of anything for a period of time elevates you but eventually it comes to an end and then what? You can either move on to pastures new or try to live off a legacy of the past.

For the rest of us, the truth is there’s always someone who’s better and someone who’s worse. Only one person can rise like Mo Farah, Usain Bolt or Eliud Kipchoge to say they’re the best in the world. Yet when you bring the three of them together, each has to accept they’re only the best in their respective events. Bolt is the best sprinter, Farah the best distance track runner and Kipchoge the best at the marathon. Being the best is event specific.

When I last watched BBC Sports Personality of the Year, a decade or so ago, they went through a list of Britain’s world champions which quickly became a list of sports you barely knew existed. A quick search pulls up a similar list from 2001 which The Guardian created. While I remember triple jumper Jonathan Edwards, rowers Cracknell and Pinsent, snooker’s Ronnie O’Sullivan and boxing’s Lennox Lewis; can anyone outside of the sports name our former world champions in waterskiing, billiards, real tennis or canoeing? This isn’t to diminish the efforts of the athletes in minor sports, only to point out how limited winning success is in its scope and recognition.

Could winning represent something deeper than simply coming first? I suspect many believe winning brings some kind of Midas touch. That it’ll turn them into a good person, bring them friends, a beautiful spouse, maybe make their lives easier by giving them power and influence, or even like King Midas bring them riches. While that may be true for Bolt and Farah, the effects of winning below the elite level quickly diminish. Whatever you might believe, the idea of outer success signifying some kind of inner worth is flawed. Many champions are still unhappy even while they’re winning. Their struggles show up time and time again, more so after they retire from competition. Winning hasn’t transformed them into happier or more secure people.

What I’m hopefully getting across is the idea that winning, in and of itself, is almost worthless. Firstly because in any race there’s only one winner and if you’re up against a vastly superior opponent you’re a guaranteed loser. Secondly winning is transitory – someone always replaces the current champion. Thirdly even if you win in your local talent pool there are others further afield who will be better. Finally because you’ve only won a specialised, measurable event; you’re one champion among many. How ever much BBC Sports Personality of the Year may want to single out someone as the champion of champions, genuinely ranking all the contenders across a spectrum of sports and athleticism is an impossible task.

If winning is worthless and, according to Ian Stewart, so is coming second then what is the point of competing?

I believe the answer lies in something we’ve all heard many times from school onwards. It’s the cliché of “doing your best” or more accurately “getting the best out of yourself”. Listening to Chris Hoy, Britain’s much decorated track-cyclist, commentate during the last Olympics, he told how he set challenging process goals for his training, recovery and all the other things involved in getting him to the start-line of races. If he could honestly say he’d ticked the box on those goals before the race started then he would be satisfied with the outcome whether it was gold, silver, bronze or whatever. He set himself challenging training targets to put himself in position to perform at his best on the day. If someone else then turned up who was fitter or stronger, he could accept it without any form of regret. While he never said it, probably because it never happened, if he hadn’t ticked the box on those process goals then he didn’t deserve to win but wouldn’t have complained if he did.

Compare that to the average runner who goes to the pub for birthday drinks when their schedule needed them to have an early night, or the runner who misses a couple of sessions in the depths of January because it’s cold or raining. Think about how these runners then rationalise and excuse themselves but also get upset when beaten over the line or missing a PB by seconds. Hoy had no need for excuses or rationalisations because he knew he’d given his best from start to finish.

This is where the desire to compete and win takes you. While you may begin with a level of natural talent that allows you to coast past your initial opponents eventually the competition becomes tough. At that point you make a choice – accept what you’ve achieved, or dig in and try for more. If you opt for the latter then you train harder, train more frequently, train more intensely. Taking the challenge to compete at higher standards will take you out of your comfort zone as you begin to try new things and look for alternative methods in your quest for success. Sometimes there’s a shortcut like buying better equipment – the new running shoes that promise to make you 4% faster. Sometimes innovation is good, sometimes it verges on breaking the spirit of the rules.

For some, winning becomes so all-consuming they take desperate measures. They break the rules – either through foul play during competition or behind the scenes like taking banned substances. Sometimes others push them into these situations like the state-sponsored doping of East Germany or the pressure exerted in sports where doping’s considered the norm. The choice to stay honest and drop out is a tough one when you’ve already invested so much of your life into something you love doing and which provides a livelihood.

Ultimately winning is being the best at a particular thing at a specific moment in time. That’s all. Nothing more. It only means something if it takes you to the next level, to new competition, gets you to push yourself harder and try new things; or comes as a result of them.

Returning to Lombardi’s quote, which as I say is often misquoted, what he actually said is “Winning is not everything, but making the effort to win is”. It’s a very different emphasis and one I’ve come to agree with.