As a coach I’m fascinated by the learning process. Having coached and participated for years, it’s very easy to forget how difficult learning new skills is. When I started doing sprint drills back in October, I got a reminder of what it’s like to be a clumsy beginner. Three months after regular repetition and careful attention, I’ve got them looking competent and am now finding nuances of technique to work on.

This is not the first thing I’ve learned recently. Just before Christmas I finally acquired another skill which I’ve been struggling with for over thirty years. I started doing The Times Quick Cryptic crossword online. Cryptic crosswords aren’t new to me, a friend first explained them circa 1990. Occasionally, whenever I’ve been sat in a waiting room or there’s a newspaper on the table, I’ve attempted the cryptic with varying levels of success. The ones in the broadsheets have always been beyond me, but I could usually do a few clues in the lesser papers.

My resurgence of interest in cryptics came from a video on Youtube and then I was helped by a daily blog which breaks down each day’s crossword. I was able to look at the answers and see how the clues had been constructed. That’s like getting a coach to help you with your running and point you in the right direction. It’s a shortcut to eliminate doubt and confusion which is a huge issue for beginners of cryptic crosswords and equally problematic when you’re a self-coached runner. When you encounter a problem in your run training, you may find ten different explanations for it online, a good coach will immediately narrow it down to two or three and hopefully pick the correct solution.

What I’d never understood is there’s a language to cryptic crosswords. Certainly I understood the mechanics of hidden words, anagrams and wordplay which is why I could solve the simpler examples. What I didn’t realise is there are many initialisms and abbreviations that crop up time and time again and you can only really learn by regular participation and repetition. To give you concrete examples from today’s; we had the letters ER representing the Queen (Elizabeth Regina), RM for Royal Marine but less obviously a letter D for the word daughter in a clue. On other days you might get MP for politicians, DE for German or EL for the Spanish word and so many more.

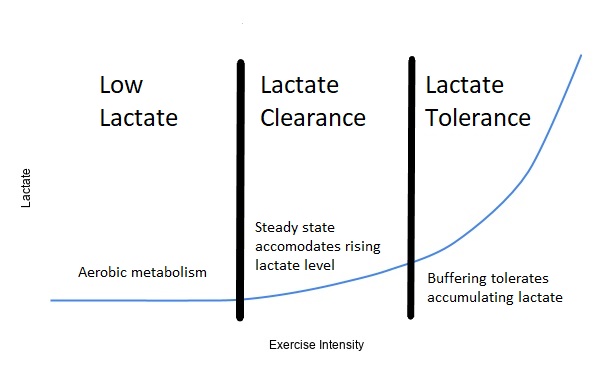

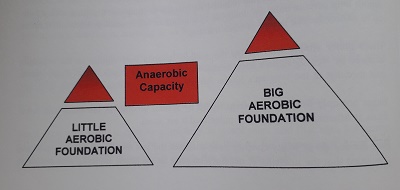

Like any language, it takes time to learn. Running has its own language words like aerobic, anaerobic, pace, effort, lactate threshold, fast-twitch muscle all have meanings which are a mystery to the uninitiated.

There is also the language of sessions – does a runner know what a fartlek is? How to do an A-skip drill? What being asked to run 4 sets of 4x200m with 200m jog recovery and 5-mins between sets means.

All languages take time to learn. It becomes more familiar, the more often you engage with it. Repetition and regular participation help you get accustomed to the language so you barely need to think about what you’re being told. Regular and frequent training get your body used to the physical language of actual movement.

When I began the cryptics it was taking two hours or more to complete one crossword. As you might guess, I had a lot of free time over the Christmas period! But I didn’t sit and stare at the crossword for two hours, I did it in 20-40 minutes stints. I’d do as much as I could, ponder the clues for another ten minutes then give up and come back later. Over the course of a day I’d get most of the crossword done in these stints and that approach is like how runners start to get faster. They do little manageable stints that total up to something approaching success. They start off running every other day for a short time. Then they lengthen the time and add in extra days. Eventually they try an interval session to break the fast efforts down into something more manageable.

Initially I couldn’t complete a cryptic without using an anagram solver, needing the online reveal to get a particular answer, or making wild guesses and checking the answer to narrow down correct letters. My first decent effort took a good 2hr30 to complete and I was super proud of myself to get it done, even if I did finish it with a little help on the last 2-3 clues. Perhaps the most significant part was what came next, it gave me confidence that I could do these damn cryptics and so I persevered.

As the week wore on, I found myself getting more familiar with the language of clues. I began to look at them as a set of words and be able to parse what answer the crossword setter was looking for me to provide. That familiarity is rather like what happens with your body as you get used to running. The first occasion you go out and run, you probably go off too quick and feel uncomfortable. Subsequent sessions you begin to know your limitations and your body begins to feel less wonky than it did. This feeling is familiar to almost any runner, even the dedicated coming back from injury.

The first time I completed the crossword without any help at all, it took me just under an hour and I did it in one stint. The following week I managed one in thirty-one minutes. The improvement was exciting, I began to get the idea I’d cracked these and I’d always be doing them in half an hour. How wrong I was. The next day I was back to wrestling with it for over an hour and a quarter. I bet there’s not a runner alive who hasn’t thought “I’ve finally got training cracked” and then been surprised when it all goes backwards a month later!

Nonetheless the general trend was upwards and in New Year’s week I recorded a time of 24:04. Of course, I was excited. The excitement was slightly dampened when, reading the help blog, it became clear many people had recorded quick times on this one. It was an easy one! But then there’s many people who come to Poole parkrun in search of Personal Bests on its fast, flat course rather than tackle the hills of Upton House or further afield.

All of this summarises to the idea you don’t have to be perfect from the get go. Getting help can quicken up your journey. Repetition and frequent attempts are fundamental to progress. Doing small, manageable stints or efforts avoid overdoing things and getting demotivated. Feeling uncomfortable when you attempt something new is unavoidable. Persistence and a willingness to keep coming back through the tough times are a must. Running is quite literally a journey.